Part 1: The Men’s Party

Introduction

The Maple Viewers is a painting on a folding screen produced during the Azuchi-Momoyama Period by an artist in the Kano School of Painting. The scenes shown are several parties enjoying autumnal maple leaves falling from the trees. This painting is housed at the Tokyo National Museum and a high definition picture can be found at the following url: https://emuseum.nich.go.jp/detail?langId=en&webView=&content_base_id=100150&content_part_id=0&content_pict_id=0

The clothing of each person in this painting is rendered in enough detail that everyone becomes instructive as to the clothing and decoration styles of the time period. However, sometimes when we see the whole picture all at once, we can be overwhelmed with all the details. Here, we can take some time to analyze each person’s clothing individually and learn about what everyone is wearing. For the people making clothing recreations, we hope to be able to make some decisions about clothing style as well.

This series of articles hopes to break down the outfits of these autumnal friends by looking at each person in turn and asking what each person is wearing this season. Our first section is the left side group of party people. These gentlemen have come up to the mountain to celebrate the season with dancing, music, and snacks. We will identify each person and then look at their outfit. We will briefly discuss each piece of clothing and the decoration on it. We will also see a simplified graphic version of each garment.

Several pictures may include color swatch panels pulled from the original images. It is important to highlight the fact that these color swatches almost certainly differ from the original color used in the painting itself. Between the original images having been produced 400 years ago and the multiple layers of digital interpretation between the original and what you are seeing on your screen right now, chromatic drift is an unavoidable reality. A lot of the colors pulled out here are probably much browner than they were originally meant to be. If we look at extant pieces of clothing and look at the methods and materials used to create clothing at the time, we can see that the color options available to the Early Modern Japanese artisans could be very bright and cheerful. Especially in the Sengoku Era, we see a great propensity for bombastically colorful fashion choices among many different levels of society.

This article includes heavy use of the words “would,” “could,” and “might.” Because the clothing shown here is part of a painting, it goes without saying that these are not real extant examples of clothing. Therefore we cannot say for sure exactly how these pieces are embellished. We can only hypothesize how such a thing could be accomplished if a similar garment were to be produced in the real world. We can draw our suppositions from extant examples of 16th century clothing, although we are not going to list each of those examples here. Enterprising readers are encouraged to seek out these extant examples from places like the Japanese National Museums, various international art museums (like the Metropolitan Museum of Art,) and various books on the matter of historical Japanese costume in order to learn about the host of amazing methods used to decorate cloth and where those methods might be employed.

Part of the purpose of this article is to help those who research and recreate historical Japanese clothing to take the opportunity to make sure they look at historical sources and determine what is actually being portrayed in order to get the best sense of period appropriate styles. The common adage applies to many artists that we should try to “draw [or recreate] what you see, not what you think you see.” Taking time to break down the individual elements of something like an outfit or single robe can be incredibly educational when trying to nail down the specific things that make a samurai look like a samurai.

The Party

The six figures in the men’s party are situated on the left side of the screen in the bottom half of the painting. They are arranged in a circle with two people providing drumming music for a single dancer. Here is the full group. We will look at each of them in no particular order.

The Drummer in Pink

On the left side of the group, a man sits with a small drum over his shoulder, playing for the central dancing figure. His hair is done in a topknot (chonmage) and he sports a pencil mustache and scraggly goatee beard. He is wearing a kosode, dōbuku coat, and hakama. Although we can’t see it, he is probably also wearing another skin layer robe underneath. He sits on top of one leg, while the other leg is standing folded in front of him.

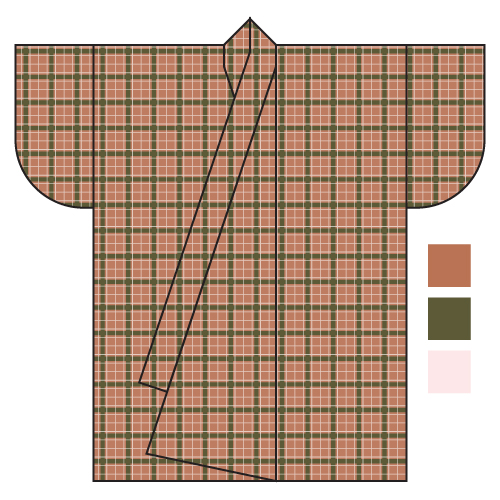

Plaid Kosode

The Drummer’s kosode is a salmon colored robe cross woven with plaid stripes in dark green and white. The bottom corners of the sleeves look closed and rounded off and the inside of the garment, as seen at the wrist opening,would appear to be a white lining. Like most kosode, the collar of the robe is the same color and pattern as the rest of the robe. Technologically speaking, plaid is a fairly easy pattern to create because it is as simple as replacing some yarn colors during the weaving process. We see plaid patterned fabric coming from cultures all across the world and in many different eras.

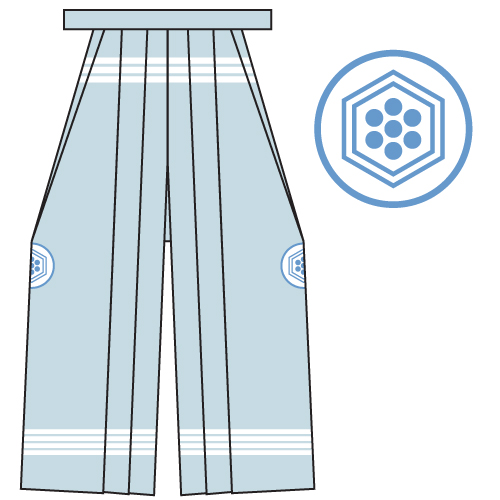

Light Blue Hakama

These light blue (asagi) hakama are decorated with horizontal stripes along the upper and lower sections of the pants. Three stripes are on the upper area and four are in the lower. There is also a rondel at the bottom of the side opening which sports a design that is likely meant to be heraldic. The stripes on this design can be accomplished with the capped shibori (boshi shibori) method of resist dyeing. Before the garment is assembled, shapes are marked out and then a line of stitching is sewn along the edges of the shape. The thread is pulled tight and the area inside the shape borders is covered with a cap (historically, bamboo shoot leaves were used, but modernly, plastic sheeting works very well.) and then the fabric gets dyed. When the fabric is set and dry, the r sista are removed to show the shapes that were not penetrated by eye stuff. The rondels would probably be done in a similar fashion, with the circle being resisted for initial dyeing and the bright blue design being either hand painted or stenciled afterward. These hakama seem like they could be dyed with thinned indigo to create a sky blue color.

The heraldic design here looks like a flower made of seven circles (which can also represent stars) with a central circle and six radiating “petals.” All of this is shown on a hexagonal tortoise shell drawn with blue lines, which is, in turn, inside a ring made of one thin blue line.

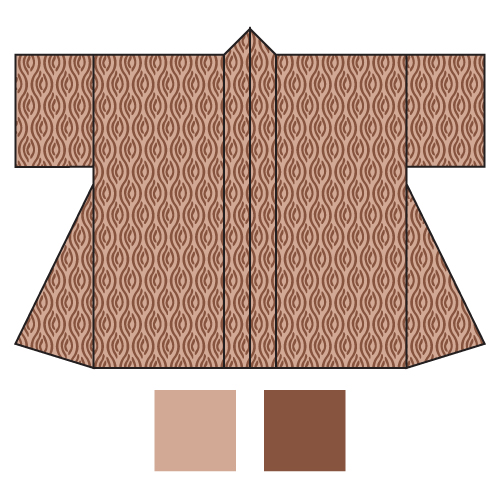

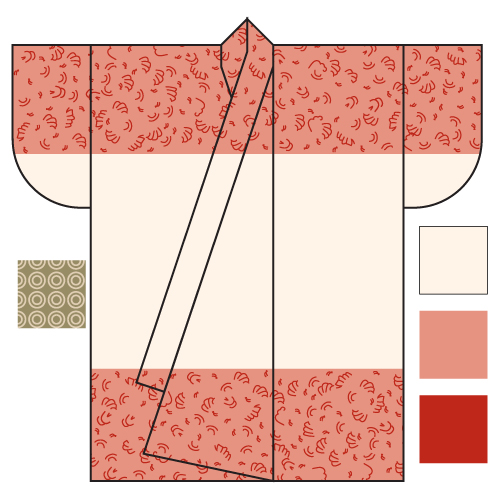

Tatewaku Dobuku

The Drummer’s coat is similar to a kosode except that it is only knee to calf length, has wide open wrist areas, and probably has some gussets in the sides to add some flared shape at the waist. It is a pale pink ground color with a “tatewaku” (vertical undulating lines) pattern in either dark red or reddish-brown. Between the vertical lines that go back and forth are oblong designs that could be leaves or simply abstract lines meant to reinforce the design. Tatewaku designs often have some sort of other design for between the vertical undulations. Designs like this could have been made with stenciled resist dyeing (katazome) or perhaps just dyed through a stencil (surizome.) Stencils, either for dye, paint, or resist paste application, were often made from paper inundated with persimmon tannins and then smoked to make it stiff and water/dye proof. Although it is not always the case on dobuku, the collar of this coat matches the rest of the garment. We can see inside some of the coat, at the wrist, that the inside looks to be lined in white. If this scene is meant to be set in the autumn (or even bleeding into winter as the E-museum description suggests) we would expect that lined garments would be in use to keep the wearers warm. Dobuku, sometimes spelled as dofuku, are the forerunners of the modern “haori” coat.

The Man in the Purple Coat

At the top right of the men’s party sits a man of maybe greater age than the rest. Like the others, his hair is tied back and spindly stray hairs stick out of the chonmage at odd angles. He has a long, droopy handlebar mustache and a goatee. Thick sideburns are disconnected from the rest of his hair.

He is dressed casually but fashionably, like his fellows, with at least two layers of kosode, a pair of hakama, and a dōbuku coat. A short sword sticks out of his coat on his left side (viewer’s right.) His clothing is layered with light blue (asagi), green, white, and purple. This color combination is seen in the extant clothing of several Sengoku Era warlords, including Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, so the combination was likely very fashionable at the time.

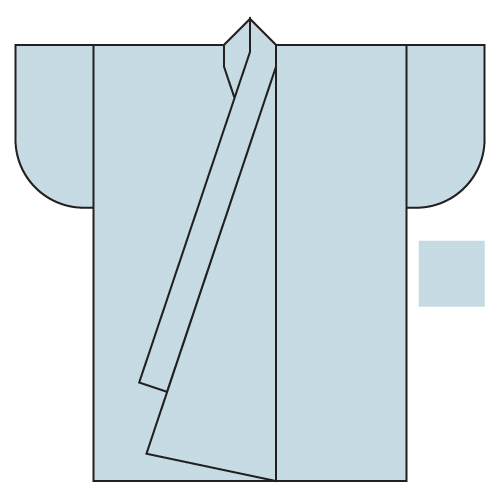

Light Blue Kosode

This blue layer robe appears mostly undecorated. It is possible that it is the bottom most layer of his outfit, but this is by no means certain. In Japanese style painting, blues and greens are often created from the mineral pigments azurite (blue) and malachite (green,) instead of the lapis lazuli or verdigris seen in contemporary European paintings. Azurite and malachite are both copper compounds and almost always naturally occur together. This, along with being cheaper to find and turn into pigment than either lapis or verdegris, makes azurite and malachite excellent and common pigment choices around the world.

Meanwhile, in the case of an actual robe, this sort of blue would likely be achieved through dyeing with indigo.

Green Kosode

Over the light indigo kosode, this man wears a green Kosode with gold designs.

Japanese language recognizes a few different kinds of green including

- Aoi (青) – a springtime blue-green. This kanji is often also translated as just “blue.”

- Moegi (萌黄) – yellow-green.

- Midori (緑) – probably closest to what an English speaker might consider to be green.

Obviously, there are going to be variations within all of these, but this robe would probably be typified as “moegi” at the time.

This kosode is covered in small golden (or yellow) swirling lines. These designs may be meant to represent some particular plant motif but at the size this image was originally made small, random, all-over swirls seem to communicate the effect just fine. Alternately, it may in fact just be a design of various non-representative swirls.

Rich members of Momoyama society could definitely employ actual gold (and also silver) in decorating clothes. Artisans could apply glue to clothing (by either stencil or freehand) and then put gold leaf onto that. Alternatively, we have ample evidence of satin stitch embroidery decorated robes with gold colored silk or couched metallic gold wrapped threads.

White Hakama

The hakama worn by this figure are white cloth decorated with what look like alternating horizontal sections of seashells and flowing water, or waves.

Multiple kinds of seashells are scattered throughout their respective sections and these are interspersed with designs of green water plants, possibly seaweed. Multiple kinds of shells are shown. We see basic clam shells, conch spirals, sea urchin shells, and some large cowries. It is possible that, even on clothing, this sort of design could be done by freehand painting motifs onto the cloth.

Between sections filled with shells are patterns of flowing lines in red meant to represent flowing water. Because of the undulating shapes shown here, these could be considered waves, although no cresting or crashing waves are shown. Waves are done as sets of a few parallel lines which run until just before they would cross with a line of the next motif. Once again, this design could be stenciled or done freehand. If it were stenciled, the entire bar might be done as a single design, rather than a series of small individual motif stencils to be placed next to each other.

Purple Dobuku

This wonderful overcoat is murasaki (紫) purple with white designs of grapevines. Murasaki is a color produced by a dye from the gromwell root which can produce a range of purples with different chromatic strengths, including the greyish purple seen here. Murasaki is also a “forbidden color” that was limited to the court uniforms of specific high ranking nobility, but this sumptuary practice was applied primarily to formal courtly costumes and not everyday wear. Certainly by the time of the Sengoku Era, we see examples of this kind of purple being used by people in many different social stations. It is of course also possible to create purple/ violet fabric by over dyeing blue and red colors together.

Designs of grape vines, leaves, and bunches of grapes, all done in white against the purple background, adorn the coat. While decorations like those on the hakama are created by putting dark colors into light fabric, instances of light colored designs on a dark ground are most often achieved by putting some sort of dye resist onto the fabric and then coloring the unresisted sections. For a situation like this coat, it is possible to use either tie-dye resist or a paste resist method to stop dye from entering particular sections of fabric.

In the case of tie dye (shibori), the long vines are likely created by sewing a running stitch of thread along a line and then pulling the line of thread very tight so as to create pressure resisted areas along the line of the thread. Basically, the fabric is squeezed so tightly that dye cannot penetrate the cloth. In contrast, the grapes and leaves can be created with capped shibori (which is explained further in the section about the drummer with the pink coat.)

Katazome dyeing is a stencil based method where either dye or (in a case like this) a thick paste meant to stop dye from entering an area is put onto fabric through a stencil (later, in the Edo period, a new method of freehand drawing using this paste, called Yuzen dyeing, would become popular) and then color is applied and set before the paste is washed out of the fabric to leave the undyed designs on the cloth.

The Man in the Black Coat

This party goer is wearing a katasuso decorated kosode with variegated green hakama and a long sleeveless black coat. Interestingly, the area under the side opening of the hakama shows a brown or green decorated fabric, which is normally an odd development. We would presume that whatever robe is being worn directly under the hakama would be the same as the top robe on the upper body. It is possible that this robe is differently colored in its top and bottom section, or this could be a mistake by the painter. We will discuss this further a little bit below.

This man has a standard chonmage topknot and a pencil mustache paired with a long goatee. Although much of his face is obscured by damage to the painting itself, we can see some very stylized ear shape. These proportionally large (and fairly wobbly shapes) ears are stylistically pretty consistent with the other men in the group and are only highlighted here by his lack of a clearly shown face.

Katasuso Kosode

The katasuso (meaning shoulders and hem) style of kimono decoration is originally an economical cheat on clothing decoration which ended up becoming very popular in fashion proper. Because garments covered by other layers of clothing would only be seen at the collar, sleeve edges, and bottom hem, robes would be made where the entire center section of the robe was left undyed and undecorated. Only a long the shoulders, including the collar area and the bottom hem of the robe would get any treatment. The striking difference of style between heavily and intricately decorated edges, with a boldly contrasting solid block of white meant that katasuso robes eventually came to be a top layer selection in their own right, instead of just a way to cheap out on dyeing and embroidery.

This example shows the characteristic white middle section with the top having a bold pink ground and red sprays of lines in either swirling loops or areas meant to look like the outlines of flowers. The red lines are probably the same kind of dye as the ground, but applied in higher concentration of pigment. To achieve this, the main robe pieces would be dyed in a shibori style where the white is completely bound off with the pink areas left exposed. In a dye method called oke-shibori (bucket shibori), large areas of cloth are enclosed in a wooden tub with a tightly fitting lid, while dyed sections are in the open air. The entire construction is then dyed together. When the fabric is taken out of the bucket afterwards, it remains clean. Then it is possible to apply designs onto the dyed areas with stencils or by hand.

Normally we would expect that the bottom section of design would begin at the knees and go down to the hem of the garment and that it would be similar in design to the shoulder area. We are presented with a conundrum, then, in seeing a decorated section just below the waist of this figure. The ground here appears to be a lighter brown with similarly shaped, although lighter colored designs when compared with the pink shoulder section. It is possible that a robe like this might have a separately decorated middle section, and this would be a comparatively rare oddity, although not an impossible one. If there were a central decorated section, we might expect it to butt up against the shoulder decorated areas, which we would then see represented on the sleeves of this figure as well. This departure from the usual style makes it seem like this detail might be a mistake on the artist’s part, but this is not a sure thing. Whether the painted section is a mistake or an accurate representation of a rarer style of clothing, the end result here is still a beautiful image.

Side Note: Another Tanbo-cho author has also suggested that this might be the lining of the garment. Sometimes, when wearing hakama, a person would take their ankle length kosode and tuck parts of it up into their obi in order to prevent the bulk of the kosode fabric from sitting in the crotch of the hakama. This practice also separates the front overlapping sections of the kosode to the sides of the wearer, allowing them more leg mobility. This would mean that the inside sections of the robe are displayed at the side hips of the wearer. This is another distinct possible fashion choice in this instance.

Green Hakama

In a real garment, the decoration on the pants would be much more proficient than they might first appear. The ground of this design is alternating horizontal bars of a light green/ rich celadon alternating with a darker muddy green. All over are designs of bent over grasses and some light colored circles and small spots. Because the circles are irregular in their shape and seem fairly oblong, it is likely that they were produced using a shibori method of pinching up a bit of fabric and then binding just the base of the bunched section. Executing this design presents a technical challenge in an order of operations to create this design and making sure none of the processes interfere with each other.

It would seem that this sort of decoration might be done in the following manner:

- Trace out all designs in fugitive (water soluble) ink. Using “aobana” ink, the artisan can draw/mark out any necessary designs. By drawing everything out first, they can ensure that none of the processes will step on any others. For example, by tracing the horizontal separation lines first, the artist makes sure that no circle or dot will overlap the banding lines.

- Sew running stitches for the bar demarcations and the solid resisted spots, but don’t bind any of them tightly yet. We can guess that the spots are done with capped shibori instead of ring shibori because they have no internal dyed sections.

- Bind up each of the rings.

- Cover and bind the spots.

- Do the first round of light green dyeing.

- After the first dyeing has dried, the sections which will remain light green need to be covered and bound as well. This can be done with either bucket resist or by wrapping the sections to be resisted around a core of some kind (traditionally, cylinders would be made by tightly rolling paper!) and covering the areas on the core.

- Do the second round of darker green dyeing.

- After all the dyes are dried and set, all the shibori sections are unbound/opened and the fabric is pressed flat.

- Finally, dark green grass motifs can be laid in by either stencil or freehand.

And only after all this is everything assembled together into a pair of hakama. Generally, speaking, the construction of Japanese historical clothing is fairly simple. The expense and difficulty comes in decorating the fabric itself

Black Coat

In comparison to the green hakama, the decoration on this coat has fewer steps, but is no less amazing. This long dobuku is made from two panels widths of fabric and has no sleeves, so it ends up being more vest-like than other dōbuku designs. The black ground is broken up by scattered densely packed spots and what looks to be a large kamon (crest) style emblem in the top center back. This kamon is an eight petalled non-descript flower with round lobed petals (Perhaps a chrysanthemum?) encircled by eight flowers with five petals each and then another flower to each side. Or at least, we can presume this design since we cannot see the entire thing. The five petals flowers could be plum blossoms since each petal has one rounded, unsplit lobe, or they may be simply generic cinquefoils. To each side of the design, three horizontal lines extend to the selvedge of the garment. These three lines would very likely also exist on the front of the garment and there might be a smaller version of the kamon on each breast of the jacket. The Momoyama era marks the beginning of the daimon style of garments, where kamon crests are placed (in large size) at the center back of a coat, kimono, or hitatare, and then in smaller size of the back of the sleeves and on the right and left breast on the front.

A subset of katazome (stencil dyeing) decoration is the komon (but not “ka-mon”) style. Katazome utilizes stencils cut from Japanese style paper treated with persimmon tannins and smoked so that it is stiff, long lasting, and waterproof. Then motifs are cut out to make a stencil. In komon style, many small designs are cut into a stencil to make a repeating pattern. This coat looks like resist paste was applied through larger stencils for the kamon and lines, and then a komon style stencil was used to resist designs onto the rest of the fabric area before dye was brushed on. Making a good strong black dye can be difficult using historical materials and methods. Multiple coats of dye might be required to make a full black dye job.

Side Note: Obviously the komon pattern in the graphic representation is different than what is portrayed in the painting itself. Making a repeatable pattern that can be spread across a shape in a vector graphics program is much easier than trying to draw out each and every equivalent dash of the brush shown in the original. It is hoped that the reader will appreciate the need for a simplification of the design in light of the time demands on the author/artist.

The Drummer in Blue

On the right side of the group sits another musician providing a beat for the dancer of the party. He wears a full kataginu kamishimo. That is to say, his vest-like upper garment (the kataginu) is stylistically matched with his hakama, making a single unified outfit. He also wears a white kosode with hand painted decorations and a red under kosode. Like the man in the purple coat his hair is done in a chonmage, he has disconnected sideburns, and he sports a long handlebar mustache and goatee.

Tucked to his side, he is playing a kotsuzumi drum which is made of a lacquered wooden body carved into a double bell shaped with leathers heads laces together on either side. The lacing holding the heads on can be pressed upon to adjust the tension of the heads on the fly, allowing the player to change the pitch of the drum while playing. Fitted into his belt is a small sword with black lacquer and gold colored fittings, a couple of small red cords hanging below the drum are likely the sagemono cords attached to the sword scabbard which are used to tie the sword in place at the man’s hip.

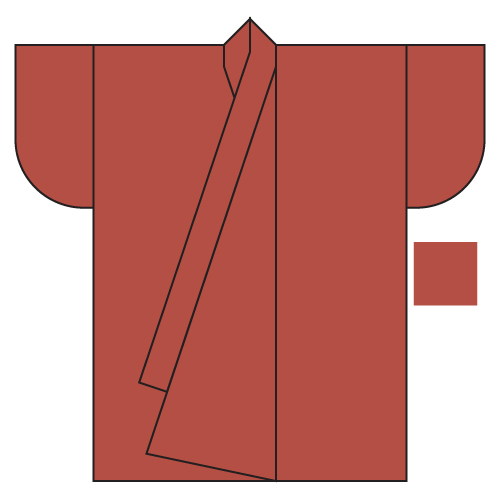

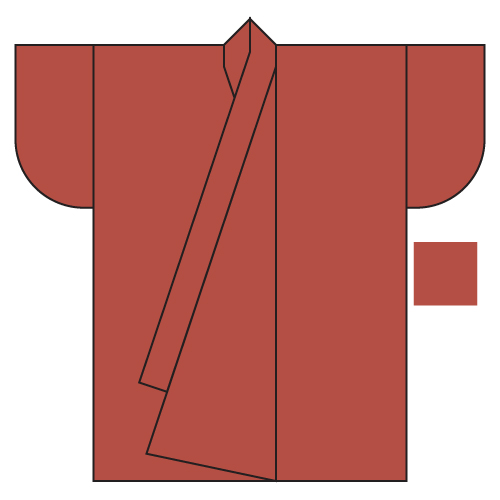

Red Kosode

This appears to be an undecorated red robe. It could be a skin layer, but maintaining a strong red color on a garment which needs to be washed more frequently than others because it is more likely to take sweat and dead skin particles would be difficult at best. However, red was considered a color which would promote good health generally and so it might not be unthinkable to have a red layer of clothing against the skin. Either way is possible, but an unseen undyed under layer would be more practical.

It may seems odd that a.person might wear a white under robe, two middle layer robes, and then an over vest and full pants, but it is worth noting that a.) the silk cloth of the period being portrayed tends to be thinner than most modern taffeta or dupioni weaves, so layering of clothing is neither as heavy nor as oppressive tomwarm bodies as we might suspect more only, and b.) this scene is set in the autumn (and according to the description from the e-museum website may also incorporate winter time activities as well) so warmer clothes might be called for when people have parties up in the mountains.

White Kosode

This kosode is left to its basic white background color but the designs of large camellias and smaller sprays of other flowers shows it to be another work of high quality. The method depicted here is one where fabric is painted in repeated passes with sumi ink (Japanese lamp black ink) mixed with soy milk as a permanent binder to the fabric. First, thinned layers of ink are applied in washes of grey to give a sense of depth and detail to the painting, and then fully dark ink is used to draw solid lines and reinforce shapes in the painting. This way, artisans are not limited to the (still bold and beautiful) ultimately flat designs of simple line art or blocks of color such as we see in most kamon designs. This painting method is also popular when painting flowers on tsujigahana decorated clothing.

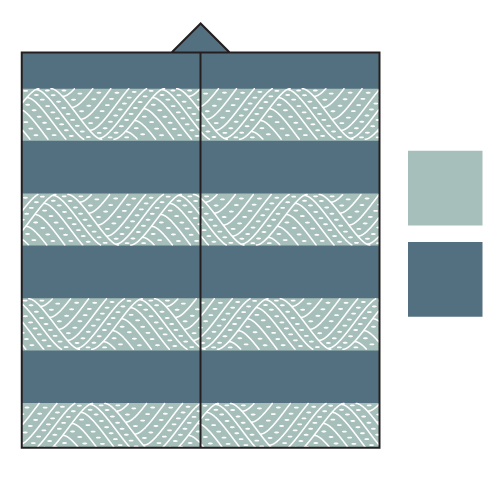

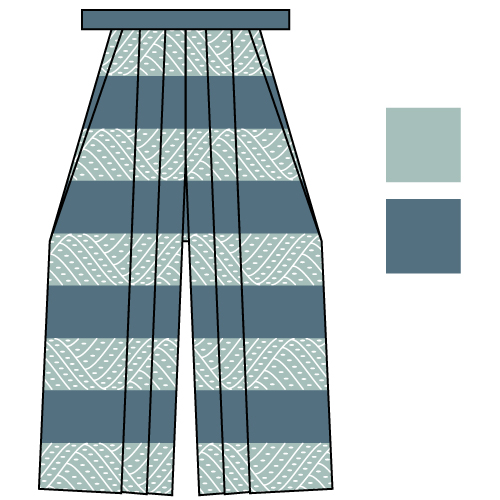

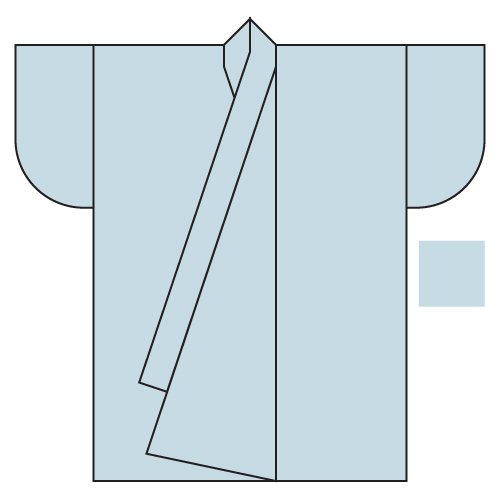

Blue Kataginu & Hakama

A kataginu is a piece of clothing made from two widths of fabric and worn over the shoulders. It is similar to a sleeveless dobuku, but the sides are left open so it is worn tucked into the waist sash or the ties of the hakama. During the Edo period, this garment would evolve dramatically into the wide winged vest so commonly associated with the samurai aesthetic, but during the time of the Momoyama, we can see that the shoulders are left softer and the front sections are not so theatrically gathered in.

It is not always a requirement of the look, but very often, a kataginu is matched in style to the hakama with which it is worn and that is the case with this person. The outfit is decorated in horizontal bands of light and dark blue. It is difficult to see with a quick glance, but the lighter blue bands are further embellished with a design of parallel lines interspersed with small rows of spots, and these sections cross against other sections of perpendicular lines so that there appears to be a stylized flowing water effect in white lines against a light blue background. This sort of design might be achieved through some clever application of both katazome and shibori effects similar to the careful order of operations shenanigans proposed with the green hakama discussed above. We also see that the flow of design continues onto the collar of the kataginu. Planning for this sort of decoration can be difficult but is often achieve by assembling a garment ahead of time with loose basting stitches, marking out all the areas to be decorated and then taking it apart for the actual process of decoration so that it may then be reassembled once it is fully suitable to be used as a finished piece.

We can also note the odd way the ties for this man’s hakama are shown. We might expect either a standard overhand bow or one of the traditional hakama knots, such as the ichi-monji or juu-monji (figures one and ten respectively), but here there seems to be some twisting of the ties around each other. It would seem that these ties are meant to be tied with friction knots where the long ties of the hakama are spiraled around each other and the tension and friction of the fabric pulling against itself keeps the whole affair firmly in place.

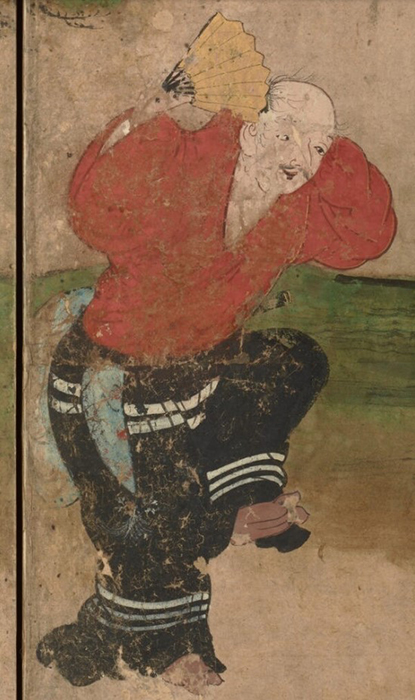

The Dancer

Toward the middle of the party a central figure entertains his compatriots with an energetic dance. He wears black hakama with white stripes over a red Kosode and another light blue Kosode with which he has partially taken off and which hangs around the back of his waist. He is using a folding paper fan of eight ribs with yellow paper as a dance accessory and he wears purple tabi socks on his feet. Very interestingly, even though he is out in nature and not on a smooth floor, he is not wearing any sandals or shoes. Elsewhere in this screen painting there are other figures who are wearing sandals to protect their feet. Also of interest is the fact that these tabi socks are not plain white. In the present day, we do not have much in the way of historical extant socks so we look to paintings like these for any explanation of contemporary styles. We can also see a small sword tucked into his belt on the figures left side.

Red Kosode

The dancer’s main top looks to be an undecorated red Kosode. Looking inside the sleeve opening we can see an area which has been painted white. This could be either lining to this same garment or a white underlayer.

Light Blue Kosode

A light blue Kosode is worn over the red layer, but has been partially removed, leaving it still tied on with sashes or hakama toes, but trailing behind the dancer. This may have been some to give the dancer a greater range of movement while dancing. It is possible that the sleeves have been tucked back into the waist to stop them from flapping around.

This robe looks like it is decorated, but because of damage to the painting itself it is difficult to determine any further details. There look to be some small spots of white, green, and red, perhaps making up some floral motifs.

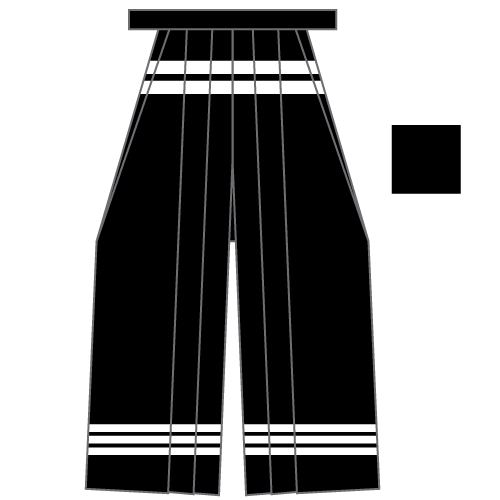

Black Hakama

These hakama are fairly plain, except for two sets of lines toward the top and bottom of the legs. The top set has two lines, while the bottom has three. As discussed above, these lines can be made using resist dye techniques.

The Man in the Green Kamishimo

This party goer is watching the proceedings while wearing a purple kosode under a highly decorated green Kataginu kamishimo with a sword tied about his waist. He is clean shaven along his face and cheeks and his pulled back hair is in a short ponytail, rather than the full chonmage worn by the other people in the group. That is to say, while most of the people in this grouping have tied back hair which doubles back on itself at least once, this figure’s hair is a simple spray out the back of the gathered area. This shorter hair and lack of facial hair might imply that he is younger than other members of the party.

Purple Kosode

Most of this robe seems to be undecorated pale purple except for a grouping of motifs on the back of each sleeve. There are three white rondels, each with a leaf right next to it. It seems like this could be something like a cotton ball (although this would be an exceedingly rare motif of it were,) a piece of mochi, an onigiri (rice ball,) or maybe a snowball. IF the designs happened to be white eggplants, that would also be a rare design, but given the coloring of the robe, would also be a clever bit of visual punning. There are multiple options and only the fact that there are small, white, round designs is certain.

It is probably that this design is repeated again on the center back of the robe, although that area is covered by the kataginu this person is wearing. If it were repeated on the back, that would be in line with the then emerging style of a single motif repeated on the back, sleeves, and breasts of the clothing.

Green Kamishimo

This kamishimo is two-toned green with decorations of grasses and waves, and what looks to be a kamon crest of crossed boat oars. The crest is shown on the top center back of the kataginu, at the bottom of the hakama side openings, and on the top back of the belt section of the hakama. It is possible that this belt area is an example of a koshi-ita back plate, although based on the fact that it does not have an angled corner anywhere, it may simply be a regular tie that simply has no knot tied over that section.

The color on this kamishimo is done in variegated light and dark green with undulating borders all over the clothing. This sort of wandering borders between sections style is meant to evoke misty clouds or sandbars in the sea. It looks like the light green areas are decorated with white (or silver?) cross crossing bent over grasses in outline. The dark green sections are harder to see but they look to have gold decorations of cresting and flowing waves. While these designs could have been done with complex shibori and gold leaf techniques, it is also entirely likely that this piece could be embroidered all over in satin stitch to make these same designs.

General Analysis

In this group of six people we see a small variety of outfit styles and a great variety of cloth decoration styles and techniques. These men seem to be members of the samurai class, but not necessarily of any very high station. They are friends together casually enjoying nature and each other’s company. The appropriate outfits for this sort of social event seem to be

- An outfit consisting of one or more kosode, a pair of hakama, and a long coat, or…

- A full kataginu kamishimo.

The decoration on these outfits is left to the personal tastes of the wearer, with most preferring bright colors, while darker colors like red or black are secondary. Red looks to be meant for an under layer while black can provide a visual counterpoint to the other lighter color options. Most popular are a slightly pale purple, light blue, and green. There are areas on clothing which are flat blocks of color mixed with others of dense decoration. Some heraldic display is present, but it does not seem to be required.

This is a small sample size, to be sure, so definite conclusions are hard to draw with any certainty. This author would like to encourage you, dear reader, to look at other pieces of art from this period and see what conclusions you can draw about the clothing of other people from this time and place in history.

This group of people are those shown in just one section of The Maple Viewers. Along with this party is another gathering of ladies and various other people scattered throughout the painting. In later articles we will take time to look at the clothing worn by these individuals and hopefully gain further understanding of the fashion of 16th Century Japan.

Practical Application

For those looking to further study historical examples and for those looking to make their own historically inspired clothing designs, we have some tools included here. Below are several blank templates of different pieces of clothing. They can be freely downloaded and colored in with whatever decorations and artist would like. They could be used to copy down designs seen in historical artwork or with someone’s original ideas. They can then be used as fashion templates for people trying to make their own historical garments.

Each template is a side by side view of the front and back of a particular garment. They are meant to be printed on US Letter sized paper in a horizontal format. Some also have markings for where a kamon might normally be placed on said garments.

Leave a comment