If you have learned western sewing techniques, there are some things that you will need to unlearn in order to create clothing with an traditional Japanese look.

Traditional Japanese sewing does not use paper patterns.

Most garments are made from rectangles, with an occasional straight diagonal line. Designs are based on narrow fabric widths (often ~14″ for hemp/ramie, ~17″ for silk). Shaping is done through belting, tucks, and adjusting the width of seam allowances.

The kantoi is a simple Yayoi period garment which consists of just two long strips of fabric sewn together (there is no shoulder seam). The majority of later garments are variations on this basic theme.

Image of kantoi from Wikimedia Commons.

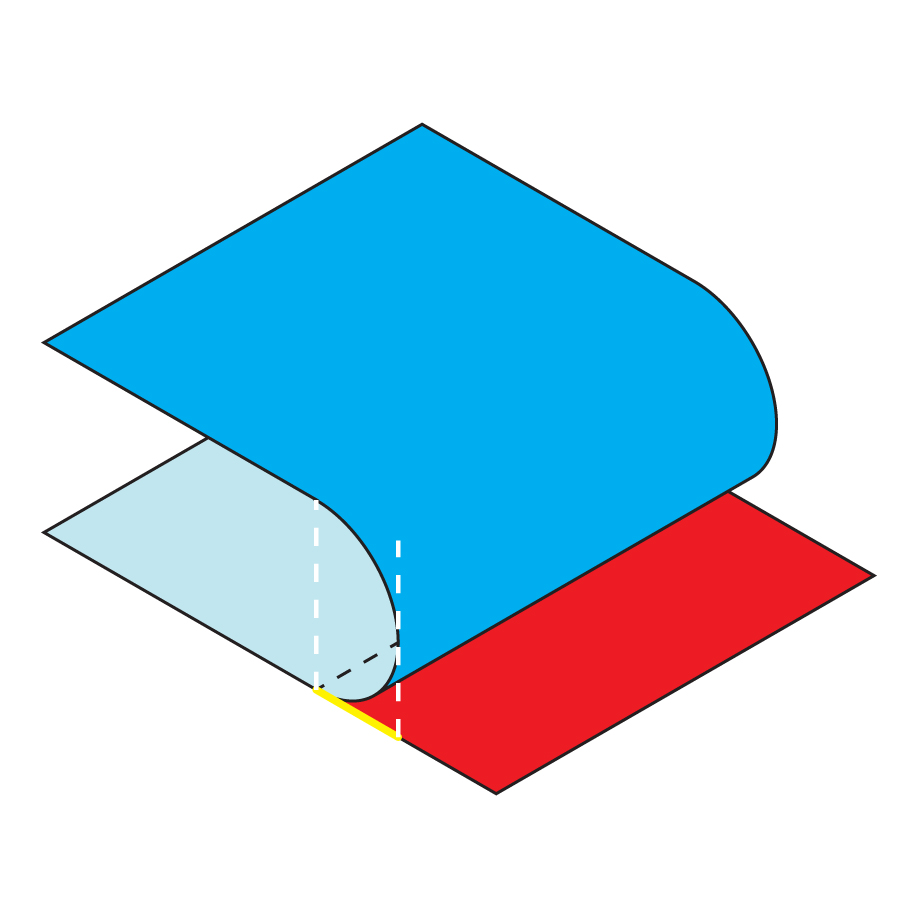

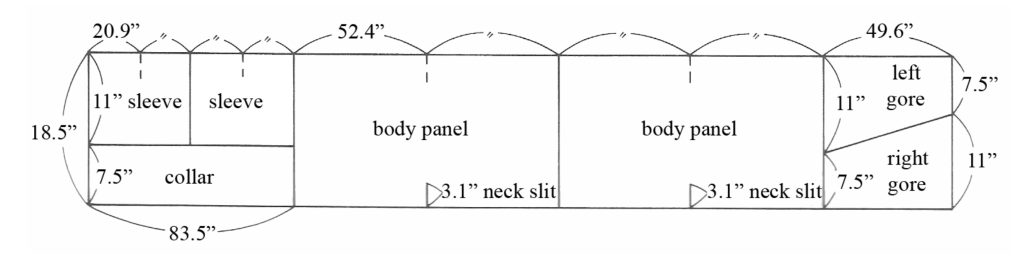

This diagram shows a width of narrow fabric folded back and forth to form a kimono or katabira, ready to cut along the red lines on the right (the curved left edges of the body panels and sleeves are the shoulder fold). Seams require minimal finishing because most are selvages.

– Five layers from top to bottom: body, (collar and overlaps), body, sleeve, sleeve.

Image from mKimono.

Garments are sewn with the intention of undoing the stitching later.

Historically, fabric was very expensive. Garments were unsewn for careful cleaning and repair, to change the location of the seam to decrease wear on stress points, to resize the garment for another wearer, or to remake the garment into something new.

This child’s Noh costume was resized by letting out the side seams, as shown by the absence of embroidery in that location.

For this reason, high-quality traditional Japanese clothing is still hand-sewn for easier seam removal. Because fast, straight running stitches were essential, they used an efficient method called unshin.

Image from Fukushokushi Zue.

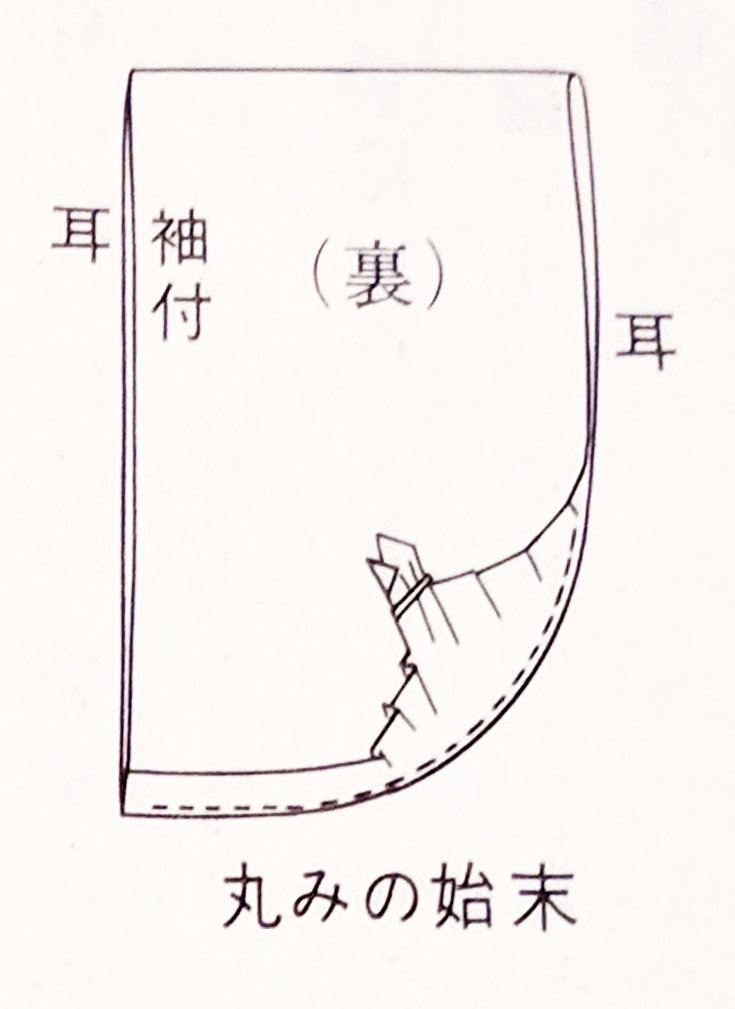

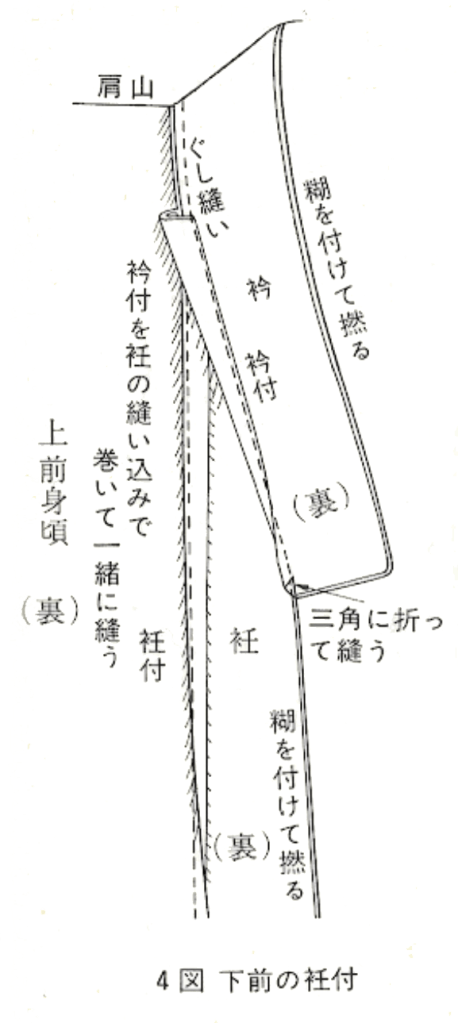

Excess fabric is not cut off.

Because garments were frequently resewn, repurposed, in need of mending, etc, cutting of the fabric was kept to an absolute minimum. Once the rectangles are cut and the neck slit made, no further cutting needs to be done. The corners of the body and overlap panels covered by the collar (shown at left) and the corners of curved sleeves are basted in place for later use. When turning something inside out, corners are handled in ways that do not involve clipping. Images from Shiryō Nihon Ifuku Saihōshi.

Seams are made as invisible as possible.

This is done by pressing the fabric ~2mm away from the actual stitching, creating a small overhanging fold to cover it. In addition to improving the appearance, it gives a slight elasticity to the seams that helps prevent them from ripping under stress.

On flat seams, this fold is called a kise (被せ, ‘cover, shelter’). At edges, the two folds are called kenuki awase (毛抜き合わせ, ‘tweezer join’).

Diagrams below courtesy of Yamanōchi Eidō.

For more information on wasai techniques, including videos of the stitches and seam treatments, check out the links below, keeping in mind that kosode use different proportions and lack some elements of the kimono such as the collar protector and shortening tuck across the back. For more information on the differences between kimono and kosode, see the Kosode Patterns post.

M Kimono Online Japanese Sewing Class

Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Craftsmanship Skills Series

Sharing Kimono Culture Project

Necessary alterations to traditional wasai techniques:

Fabric with a width of ~14-17″ is both harder to find and usually more expensive than 45″ or 58″ widths. If you choose to use a larger width, several alterations to the traditional methods are necessary.

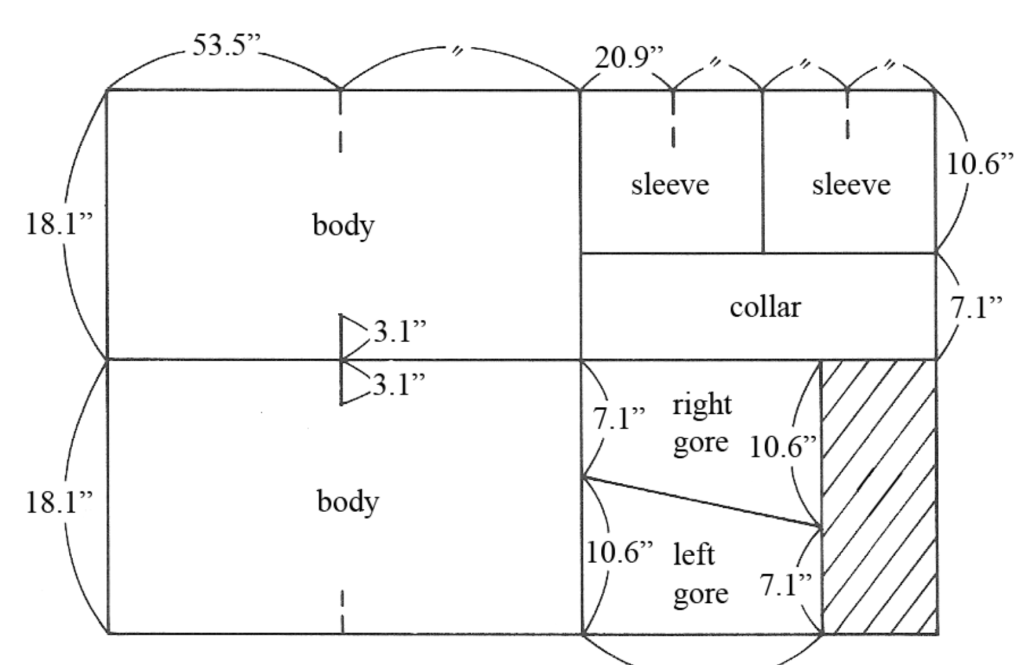

First, you will need to design a fabric layout that creates pieces of the same sizes. This is not going to be perfectly fabric efficient in the way that the original fabric layout normally was. The images below show the layout of an upper class Momoyama period silk kosode on an 18.5″ width vs its lining on a 36″ width (dotted lines indicate the shoulder fold). Diagrams translated from Jidai Ishō no Nuikata.

You may want to pre-finish the vertical edges that do not have selvages so that you don’t need to alter the sewing method any further. The method you choose will depend on the characteristics of the fabric you’re using – practice on a scrap before applying the method to the whole garment. Options include serging, zigzag stitch, cutting with pinking shears, or ripping the fabric to create a frayed edge. Ripping can pull fabric off the grain, so if you use this method (silk habutae often rips well), be sure to wash and press the fabric to correct any skew before you begin sewing.

If you don’t pre-finish the edges, you’ll need to choose another method to finish the seam allowances. Turning the edge under and slip-stitching it down works fine for most fabrics, but requires a lot of hand-sewing. French seams are durable, but require some planning ahead to deal with the places they intersect, and can add bulk. Machine blind-stitching can work well.

Alternatively, you can line your garment. This was the norm for silk kosode during fall, winter, and spring; because the lining was not decorated (before 1600), it could be more easily washed or replaced than the outer layer. Today, this is a great opportunity to machine-sew the majority of the seams without having it look obviously machine-sewn.

Regardless of which combination of historic and modern methods you choose to use, understanding the original construction and functionality of the garment will make the sewing process easier and improve the final look.

References:

- Horikoshi, Sumi. Shiryō Nihon Ifuku Saihōshi. Tōkyō: Yūzankaku Shuppan, 1974.

- Kurihara Hiro and Kawamura Machiko. Jidai Ishō no Nuikata. Genryu-sha Joint Stock Co. Tōkyō: 1984.

- M Kimono Online Japanese Sewing Class. https://jp.mkimono.tv/en/ Accessed 5/25/24.

- Ōtsuka, Sueko. Hajimete no Wasai. Seibidōshuppan, Tōkyō, 1993.

- Stinchecum, Amanda. Kosode: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection. Japan Society and Kodansha International, New York and Tōkyō, 1984.

- Tōkyō Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan. Nihon no Bijutsu #67, Kosode: Traditional Japanese Dress. Tōkyō-to: Shibundō, 1966-.

- Tōkyō Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan. Nihon no Bijutsu #435, From Kosode to Kimono. Tōkyō-to: Shibundō, 1966-.

Leave a comment