Historically speaking, fabric color and decoration have been a language describing your wealth and social class as much as your personal taste. Peasants were likely to wear inexpensive and practical dye colors such as yellow, brown, blue, and black, regardless of the exact time period. Since the Heian period, aristocratic (kuge) women’s clothing has been strongly influenced by seasonally-specific kasane no irome (‘layered colors’), while kuge men’s clothing followed its own color rules representing court rank. Both of these types of aristocratic clothing primarily consisted of ōsode, garments with huge wrist openings, dyed before weaving (saki-zome) to create complex weaves and fabulous brocaded designs.

As the samurai class rose to power during the Kamakura period, followed by the artisan/merchant class during the Muromachi period, a complex middle ground developed in fashion. The middle class could afford only a moderate number of the newly popular kosode (garments with small sleeve openings), and so the garments became more likely to be dyed after weaving (ato-zome) with multicolored, multiseasonal motifs.

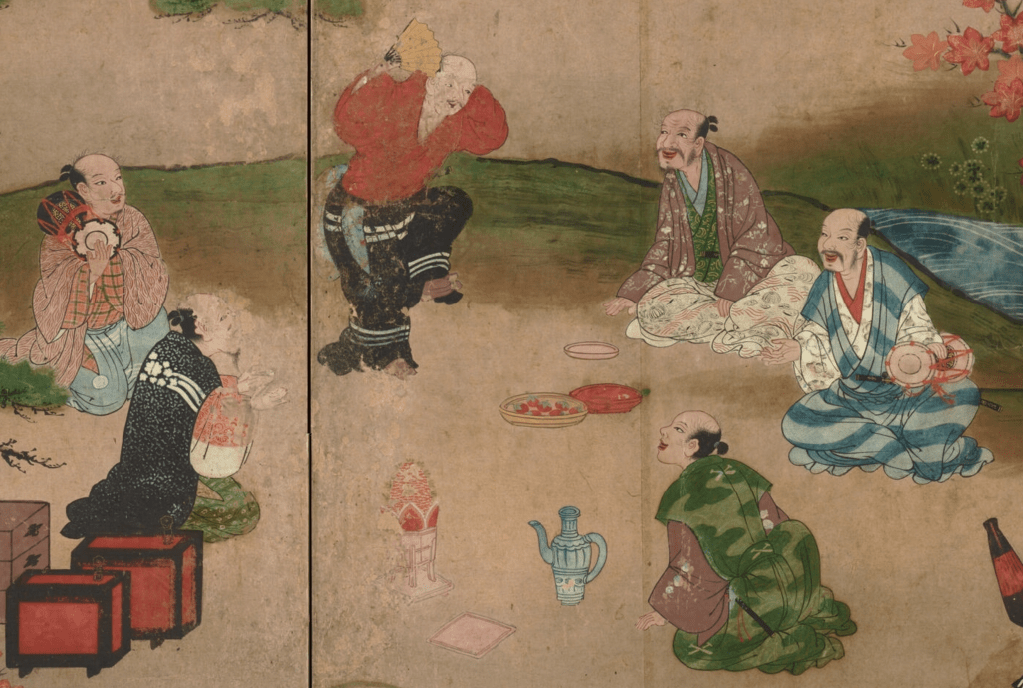

The upshot is that if you want to design an ensemble in historically plausible colors, there is no single easy set of rules to follow. The most reliable way to create a convincing ensemble is to find images depicting your desired social class, time period, and gender presentation. For reference images, please see the Fashion References by Era post. Another good option would be to choose an ensemble from the Kyо̄to Costume Museum or the Kyо̄to Dyeing and Weaving Association. You will notice that in contrast to Edo period clothing, dominated by subdued colors and vertical stripes, medieval Japanese clothing more commonly includes bright colors, horizontal stripes, plaids, and floral prints, often all in the same ensemble.

Sumptuary regulations varied by time and region, and were sometimes poorly enforced, especially during times of civil war. Proscribed colors (kinjiki) were typically described very precisely; for example, purple in general was not restricted, but koki-murasaki was, defined as a specific extra-dark shade of purple produced from the shikon root. Precise color names are an element that is literally lost in translation, which is why it is important to go back to the original Japanese-language text rather than trusting English-language summaries of sumptuary regulations. In addition, favored courtiers could be granted permission to wear some kinjiki.

The traditional Japanese color palette (dentо̄shoku) was determined by the natural dyes available, but an exceptionally wide variety of colors were produced, including fluorescent and iridescent dyes. The expense, and therefore prestige, of various dyestuffs varied according to their physical properties, such as the amount of dyestuff needed, its tendency toward fading, and color change in response to pH. As a result, wealth and youth were characterized by brighter, more expensive colors such as fire engine red and deep purple, while age, poverty, religious vows, and mourning were associated with more subdued, practical colors such as brown, navy, and black. For the same reason, underlayers were normally white, as many dye colors (particularly red and purple) would be adversely affected by sweat and laundering. Sometimes a non-white collar will appear to be the closest layer to the skin, but there was typically a white layer underneath that was not visible, equivalent to the modern hadajuban.

More information about Japanese dyes: “Japanese Dyeing“

- Red: Commoners sometimes used madder (brick red), while the wealthy used madder, sappanwood (raspberry red) and safflower (fire engine red). Safflower was the most expensive, and was especially popular with young upper class Momoyama women.

- Orange was made using any red plus any yellow, or a red with an acidic modifier. Some extant garments that now appear orange were originally red.

- Yellows included gardenia (daffodil yellow), Amur cork tree (fluorescent yellow, often used to create bright greens) and the popular miscanthus (a tastefully subdued golden yellow).

- Greens were made using any yellow plus indigo, or by adding iron to yellow. Men were more likely to wear dark green, while women more often wore lime green.

- Blue was dyed using indigo, primarily from dyer’s knotweed, and was especially popular among commoners and samurai due to its properties of strengthening the fabric and repelling insects.

- Purple could be made either from the shikon root (murasaki) or from a red plus indigo or iron (false murasaki/nise murasaki). Lavender and red-purple were common among the middle and upper classes. Dark shades of true murasaki were restricted during some time periods.

- Browns were made from tannin-containing plants such as oak and chestnut, and were worn by men and women, rich and poor. Brown could be turned into gray or black through the addition of iron.

- White was commonly used painted or stenciled with a design. Solid white hakama and kosode were seen as part of otherwise colorful ensembles or specific ranks of courtiers and servants, but head-to-toe solid white was generally used for specific purposes, such as designated professions, religious or funeral use.

- Black was worn by religious, charcoal sellers, and farmers. Patterned blacks were worn by samurai, and after ~1595 by noblewomen (Keichо̄ period).

When looking at extant garments and textile fragments, keep in mind that dye colors can fade significantly over time, and iron mordant will degrade and darken silk. The original garments were often very brightly colored.

References:

- Cardon, Dominique. Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science. London: Archetype, 2007.

- Ito, Toshiko. Tsujigahana : The Flower of Japanese Textile Art. Kodansha America, Incorporated, 1985.

- Kaneko, Kenji. Katazome, Komon, Chuugata. Kyoto: Fujioka Mamoru, 1994.

- Kyoto Dyeing and Weaving Association. https://senshokubunka-kyoto.jp/gijyutu/ Accessed 2/13/24.

- Nakano, Eiko and Barbara Stephan. Japanese stencil dyeing: paste-resist techniques. New York: Weatherhill 1982.

- Stinchecum, AM. Kosode: 16th to 19th Century Textiles From the Nomura Collection. Japan Society and Kodansha International, 1984.

Leave a comment