Sewing

- Needles (hari/針)

- Spool of thread (itomaki/糸巻き, odamaki/苧環, kuda/管, tama/玉)

- Ring thimble (yubinuki/指貫)

- Third hand (kakebari/掛け針)

- Needle threader (ito-tōshi/糸通し)

Cutting and Piercing

- Scissors (nigiri basami/握り鋏)

- Knife (monotachigatana/物裁ち刀)

- Chisel (wanomi/釦鑿)

- Awl (me–uchi/目打ち, senmaidōshi/千枚通し)

Measuring and Marking:

- Ruler (kujirajaku/鯨尺, typically comes in 1, 2, 3-shaku lengths)

- Marking creaser/spatula (hera/箆)

- Temporary ink (aobana/青花)

- Sleeve rounding template (sode marumi katachi/袖丸み形)

Storage:

- Needle case (hariire/針入れ)

- Broken needle case (orehariire/折れ針入れ)

- Sewing box (haribako/針箱)

Other:

- Thread-pulling tweezers (itonuki/糸抜き)

- Pan-shaped iron (hinoshi/火熨斗)

- Weight (bunchin/文鎮)

- Embroidery frame (shishū-dai/刺繍台)

Needles (hari)

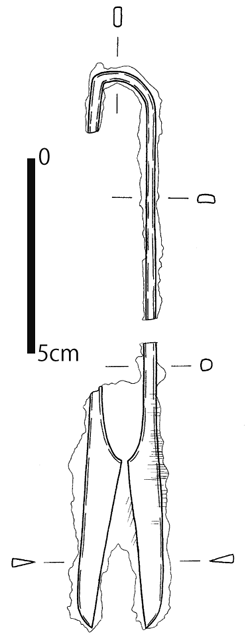

Bone and antler needles can be found in early archaeological sites; their use faded out gradually as metal needles became more readily available. Metal needles dating from the 8th century are stored in the Shōsōin Imperial Repository, but these are ritual needles around 20 cm long. (Imperial Household Agency). An early metal needle, probably Jomon period, can be seen in the image of bird bone needle tubes below.

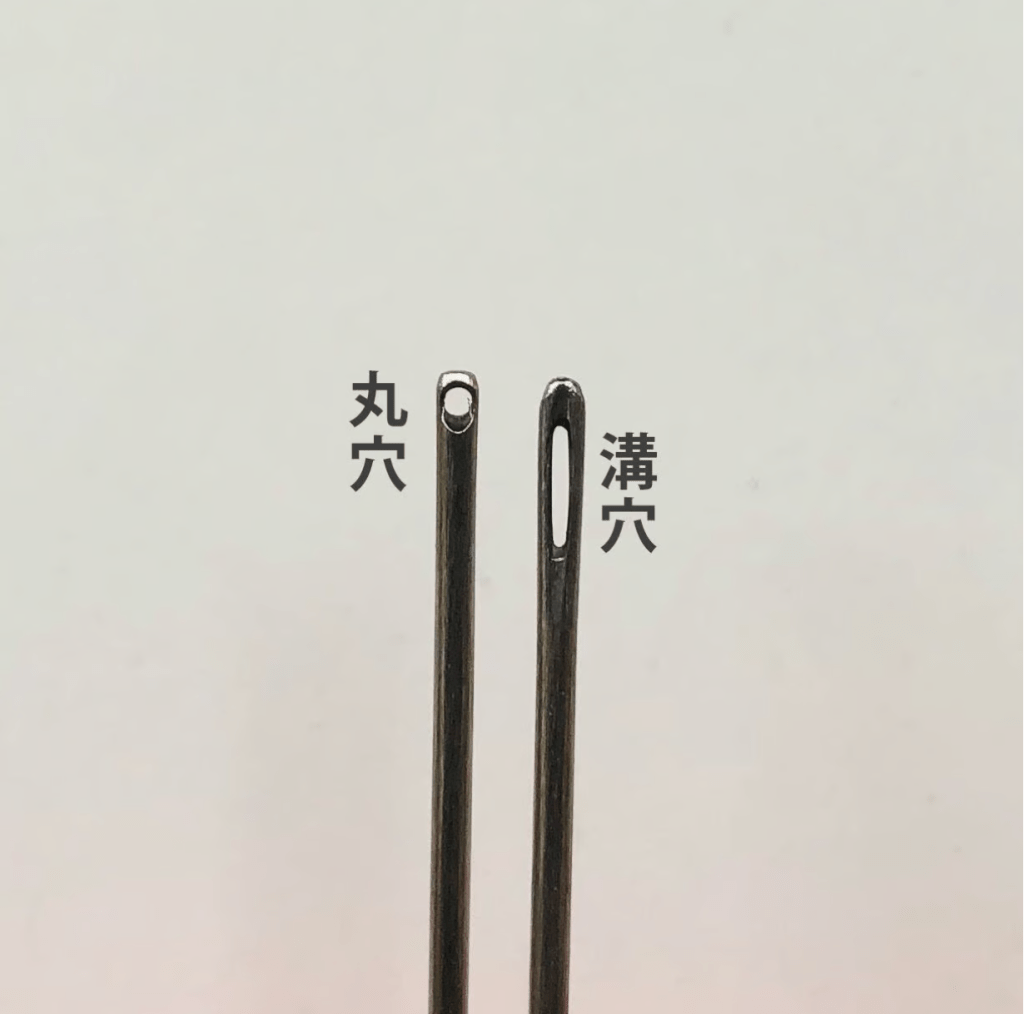

Larger-scale metal needle production began in the city of Harima in the 11th century, but the most famous type, Misuyabari, originated in Kyōto in the 14th century and began to supply the imperial court in 1651. These early needles feature a straight taper with no widening at the eye, lengthwise polishing, a triangular cross-section, and often (though not always) have a round eye rather than grooved. This traditional style of Japanese needle is considered ideal for fine sewing and embroidery even today, leaving minimal needle holes in silk. Misuyabari needles can easily be purchased online.

Needle size guide: the first number is needle thickness, and the second is length.

- 3-x is for cotton, 4-x is for silk

- x-5 is long, x-2 is short

- 4-2 or 4-3: usual needle sizes for making silk kimono

Spools (ito-maki)

One of the most common spools seen in medieval illustrations is the frame spool (waku–itomaki, ‘frame thread-winder’, also known as odamaki, ‘hemp winder’). Functionally, it is very versatile: it spins freely around a central axis, and can be used for reeling silk or for steaming newly-spun thread to set the twist.

The type most commonly called itomaki without any other descriptors is a small square bobbin, often with inward-curving sides. Both of these spool shapes are used in kamon motifs.

Straight cylindrical spools were called kuda, ‘tubes’, and could be made of slender bamboo or wood dowels. Later variants included rounded ends, which can now be purchased in shibori supply shops as “koro”, ‘cores’.

Spools with a compact shape and heavier weight are called tama (‘balls’), and are generally used for weaving or braiding rather than sewing. Tama are still sold for use with marudai and other braiding stands.

Thimble (yubinuki)

Today, the term yubinuki describes all types of thimble, but as of the 1200s, it specifically described ring thimbles. “Yubinuki: A loop made of leather or metal that is put on the finger to press the head of the needle in sewing.” Excerpt from the dictionary Kanchiinbon Myōgishō/観智院本名義抄 (1241).

Here is a tutorial on how to make and wear a simple leather ring thimble (yubigawa/指皮). https://jp.mkimono.tv/yubinuki/ Colorful thread-wrapped ring thimbles (kaga-yubinuki) were not developed until after 1600.

A ring thimble is used during the rapid hand sewing technique called unshin (運針).

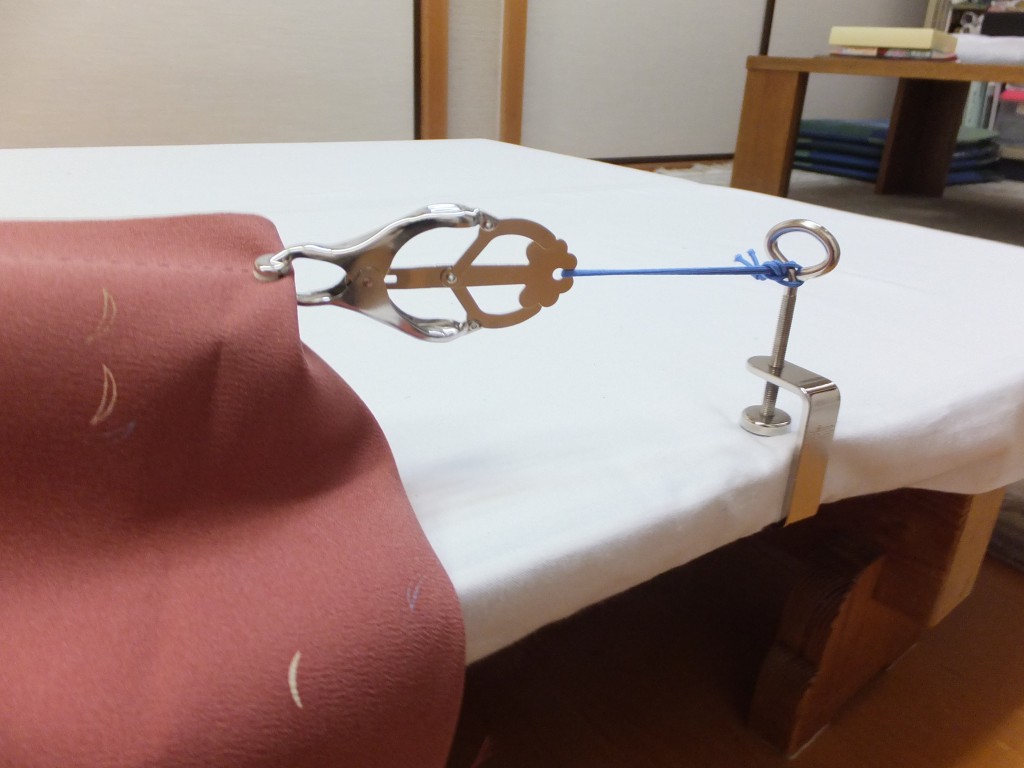

Third hand (kakebari)

Kakebari translates as ‘hanging needle’. Historically, a needle was simply inserted into the fabric, and a loop of cord held the end of the fabric under tension for ease of stitching. Today, clips called anzen kakebari (‘safety kakebari‘), also known as a ‘third hand’, are used for the same purpose. I have not found evidence of pins or pincushions in medieval Japan; the kakebari serves a similar purpose in holding the edges aligned.

The source for the images below, Moriwasai Kobo, is a traditional Japanese sewing and alteration business in Nara.

Needle threader (itotōshi)

Japanese sewing tutorials often recommend using a strand of your own hair to thread a needle with a small eye.

Scissors (nigiri-basami)

“The types of nigiri basami/握りばさみ are, from the left in the photo, the turnip shape/かぶら型 (Kyoto style/京型), the boat shape/舟形 (eastern style/東型), and the Kansai style/関西型 (western style/西型). The reason why the length and width of each blade is different is that the thickness and type of cloth used differed depending on the climate of each region.” (Hiraoka)

Knife (monotachigatana)

The term “stuff-cutting knife” (monotachigatana) is still found in some Japanese dictionaries, but no longer appears to be sold under that name. Similar blades can be found by searching for kogatana/小刀. Please note that this is not the same blade shape as a kiridashi.

Left: A woman cutting fabric for an obi by holding a fold taut between her hand and mouth and pulling a monotachigatana along the fold, 71-ban Shokunin Utaawase E.

Chisel (wanomi)

A chisel is a quick and easy way to cut slits for lacing, and chisels are still sold in Japanese sewing supply stores. Place a cutting surface underneath and tap the end with a mallet.

Right: Modern Japanese sewing chisel, Bunka Business Bureau

Awl (me-uchi, senmaidōshi)

A me-uchi (left side, ‘hole punch’) has a rounded tip. It’s used to help with delicate tasks like thread removal and turning corners, and can be used to gently create holes in looser fabrics, spreading the threads apart rather than cutting them so that cord can pass through.

A senmaidōshi (right side, ‘pass through many layers‘) is more pointed, and is used to create holes in more stubborn materials or through many layers.

Image from Ando Mishin, Rakuten.

Ruler (shaku, kujirajaku)

Whale baleen and bamboo were the traditionally preferred materials for Japanese rulers. The waxy surface of bamboo prevents ink from adhering unless it is scratched, so a marking template (katagane) was placed, then a sickle-shaped blade (kama) was used to scratch the lines. The marking dots used on Japanese rulers are called hoshi/star/星.

The length of various measuring units and the width of fabric bolts were not standardized until after 1600. The kujirajaku (‘whale measure’) was about 38cm, and the gofukujaku (‘clothing measure’) was about 36cm. However, the actual width of bolts of plant-based fabric (hemp, ramie, cotton) was about 35 cm, and the average width of silk was over 40 cm (Nagasaki 2023); different cutting layouts were used for the different fabric types (see Kosode articles).

Marking creaser (hera)

Bone creasers (hera) are a very versatile tool, used worldwide in sewing, bookbinding, leatherworking and more. The basic design has survived for millenia with many variations in shape and material. For sewing, pressure is applied with an edge in order to create a dent. This dent marks locations on a piece of fabric in a similar way to a fabric marker, but marks both sides and multiple layers simultaneously. This convenient characteristic means that hera remain popular sewing tools worldwide to the present day. In addition, the rounded side can be used to flatten seams using a motion similar to burnishing.

Temporary ink (aobana, also known as tsuyugusa)

Aobana means ‘blue flower’; the water-soluble ink is stored by infusing squares of paper with the juice of these blue flower petals (Commelina communis). The blue paper is later placed in water to create a temporary marking ink, applied with a brush. Modern blue fabric markers were invented to imitate its vivid color and and easy washability. For more details, check out John Marshall’s website.

Sleeve rounding template (sode marumi katachi)

Sleeve rounding templates are an essential part of modern kimono construction. I have not found evidence as to whether or not they were used before 1600. If so, they may have been made from multiple sheets of washi paper laminated together using persimmon tannin (kakishibu) or seaweed glue (funori).

Needle cases (hari-ire)

Needle tubes (haritsutsu) and other needle cases (hari-ire) were developed very early and can be found in a wide variety of materials and styles.

Broken needle case (orehari-ire)

Orehari-ire are needle cases specifically intended to hold unusable needles until they could be laid to rest at the needle memorial service (Hari-Kuyō). A hall dedicated to the memorial service was built at Horin-ji Temple by Emperor Seiwa, so we know that some variant of the needle memorial service existed in Japan in the latter half of the 9th century. In this rite, old needles are thanked for their service, embedded in a soft piece of tofu or konnyaku, and buried. Legend has it that needles not treated in this respectful way could become mischievous and sometimes angry spirits called tsukumogami.

Sewing box (haribako)

If you look for haribako (‘needle boxes’) today, you’ll typically find modern versions with drawers. Before 1600, sewing supplies would have been stored in simple boxes called tebako (‘hand boxes’). These were used to hold a variety of everyday items including cosmetics and sewing supplies. The construction and decoration varied widely, from the gold lacquerware used by aristocracy, to simple red and black lacquer, unfinished wood, or basketry in the same lidded-box shape. The design could also include interior trays for further organization.

Thread-pulling tweezers (ito-nuki)

These cosmetic tweezers are constructed very similarly to the thread-pulling tweezers (itobatsu) which are still sold in Japanese sewing supply shops.

Modern itobatsu typically flare at the tip. I suspect the medieval version did not, both because I haven’t yet spotted that design so early and because a pair of tweezers closed with a loop could have doubled as a bodkin for the insertion of drawstrings.

Pan-shaped iron (hinoshi)

Hinoshi are found in some of the earliest archaeological sites such as kofun burial mounds. These long-handled metal pans are intended to be filled with coals and passed over the fabric to remove wrinkles. Finger-pressing and flattening using the hera are also commonly used in kimono construction.

The trowel-shaped irons (kote) popular in modern kimono construction are comparatively new, dating from the 1900s.

Weight (bunchin)

The word bunchin refers to a paperweight, including the kind that hold paper in place during calligraphy. I have not yet spotted sewing weights in medieval illustrations, but calligraphy weights were in common use, and the weights are essential for modern kimono construction, so I think there’s a good likelihood that some type of weight was used. Medieval versions may have been improvised rather than designed specifically for the purpose. Calligraphy paperweights are made from a variety of materials, including metal, stone, and particularly dense wood.

These weights are used to prevent the fabric from shifting during marking or pressing, and to hold the end so that the length can be pulled straight. The weights are often covered in fabric or leather to protect the fabric of the garment.

Embroidery frame (shishūdai)

This basic rectangular wooden embroidery frame has several variations. If you would like to see construction details or purchase one, search for ‘traditional Japanese embroidery frame’: 日本刺繍伝統的な刺繍台.

References:

- “Iroha of the family crest: About Itomaki.” https://irohakamon.com/kamon/itomaki/ Accessed 2/21/24.

- Masayuki Okamoto. “Cultural History of Things and Humans 33: Scissors”. Hosei University Press: Ichihara, 1991.

- Moriwasai Kobo. “Kukedai and Kakebari“. https://www.mori-wasai.com/post217/ Accessed 3/18/24.

- Nagasaki, Iwao. “A study on the “white horizontal striped cotton katabira” (private collection) for the Masuda Genshosho: Actual state of cotton use by upper samurai families in the Azuchi-Momoyama and early Edo periods.” Bulletin of the faculty of home economics Kyoritsu Women ‘s University Volume 69, p. 1-20, Publication date 2023-01.

- “Nigiri basami”. https://www.city.ichihara.chiba.jp/maibun/tenji132.htm Accessed 3/18/24.

- Omura, Mari and Kizawa, Naoko, “The Textile Terminology in Ancient Japan” (2017).Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 28. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/28

- Tokoro Research Laboratory. https://www.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/t_collection/en/index.html Accessed 3/18/24.

- Watanabe, Shigeru. 日本縫針考 / Nihon nuibari kō / Reflections on the Japanese sewing needle. 文松堂出版, Tōkyō, Shōwa 19 [1944] / Bunshōdō Shuppan, Tōkyō, Shōwa 19 [1944].

Leave a comment