Nara period:

In 719, Empress Genshō issued an edict regarding auspicious directions「壬戌初令天下百姓右襟」(『続日本記』巻八) . This simultaneously established the current system of wrapping garments with the left side of the collar on the exterior (ujin) for the living and the reverse (sajin) for the dead, and wrapping items with a piece of cloth as shown on the left for the living, and as on the right for the dead.

A variety of wrapping cloths were placed into the holdings of the Shōsōin Repository in the year 756. They were labeled using the terms 裹 (tsutsumi or ka, “wrap”) or 幌 (kō or horo, “canopy” or “cloak”). Some of these cloths have a strap sewn to one corner to secure the wrap in place, and many have the contents written on the cloth in ink.

This tsutsumi was used to wrap a priest’s robe (kesa) for storage. It is sewn from two pieces of silk woven in a patterned twill, and measures 108x156cm. The indigo dye is still vivid well over 1,200 years later.

Heian Period:

Wamyō Ruijushō, a dictionary of Chinese characters written in the 930s, uses the term 衣包 (koromo-tsutsumi, “garment wrap”). Masasuke Shōzokushō, a book of rules governing attire published in 1175-77, refers to 平裹 or 平包 (hira-tsutsumi, “flat wrap”) and reiterates the direction of wrapping established in the Nara period.

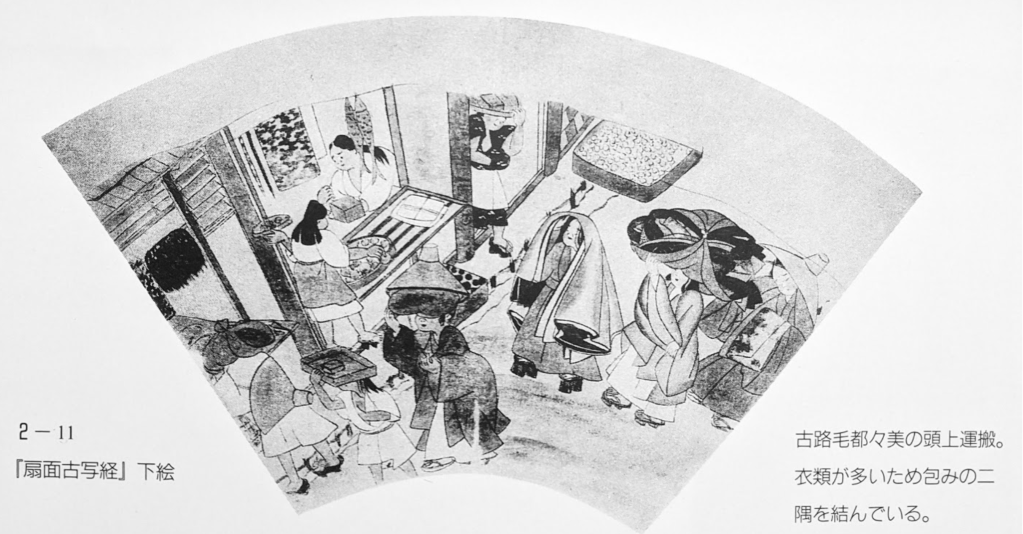

The image below of the fan-shaped Lotus Sutra belonging to Shitennoji Temple (1152) depicts the use of tsutsumi in everyday life: a large square or rectangle of unpatterned fabric is knotted together at the corners and then carried on top of the head (sometimes under a hat) or slung over the back.

Kamakura Period:

During the Kamakura period, public baths became increasingly common. One could take “merit baths” (kodoku-buro) at local temples such as Tōdaiji as part of Buddhist ritual purification. The Azuma Kagami describes Minamoto Yoritomo providing “charity baths” (seyoku) for a hundred people every day for a hundred days in 1192 in honor of the recently deceased retired emperor Go-Shirakawa. Yoritomo began a tradition of hosting visiting daimyō at his bathhouse at Kamakurayama, and is known to have engaged in a long series of baths in honor of his wife Hōjō Masako.

In 1321, a public “penny bath” (sentōburo) was established at the temple called Unkyoji.

This increase in communal bathing, particularly among the samurai class, encouraged the creation of tsutsumi with distinctive patterns so that it was easy to identify your own bundle of clothing after bathing.

Images from Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, late 1100s.

Muromachi-Momoyama Period:

Communal bathing continued to increase in popularity. In addition to temple baths, many neighborhoods had public bathhouses, and private bathing parties became a common form of recreation among the samurai class, complete with food, sake, incense and entertainments. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, Hino Tomiko, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu were all noted for their lavish bathing.

The earliest record we have of a tsutsumi being referred to as a furoshiki (bath square) is in 1616, when an inventory of Ieyasu’s possessions (駿府御分物帳) was conducted upon his death.

In conclusion:

Throughout most of Japanese history, wrapping cloths were referred to as tsutsumi rather than furoshiki. These pieces of fabric could be small or large, square or rectangular. They could be left undyed, dyed a solid color, or dyed in patterns using common techniques of the time such as shibori or katazome, and various pieces of fabric could also be patchworked together to make a larger square.

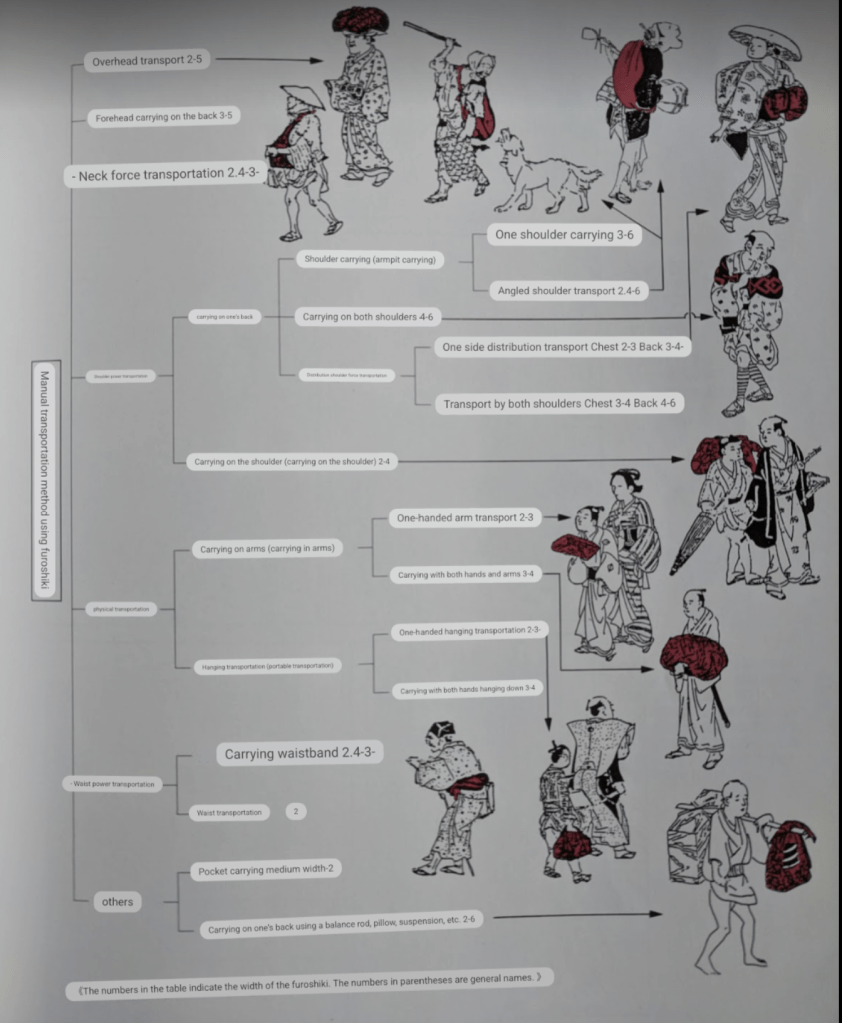

As the following image from Takemura’s Furoshiki: Japanese Wrapping Cloths shows, tsutsumi could be carried in a wide variety of ways, and their widespread use continued through the early modern period. Today, furoshiki are making a comeback both in Japan and globally as a trendy, eco-friendly alternative to disposable bags.

References:

Butler, Lee. “Washing Off the Dust: Baths and Bathing in Late Medieval Japan.” Monumenta Nipponica, Volume 60, Number 1, Spring 2005, pp. 1-41.“Shosoin: Imperial Household Agency.” http://shosoin.kunaicho.go.jp/en-US Accessed 12/7/19.

“History of Furoshiki.” https://www.miyai-net.co.jp/furoshiki/history/ Accessed 3/15/2024.

Takemura, Akihiko. Furoshiki: Japanese Wrapping Cloths. Tokyo: Nichibo Shuppan, 1994.

Leave a comment