As the lady of Yodo Castle, defender of Osaka Castle, and second wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Chacha (also known as Yodo-dono or Yodo-gimi) was a fashion icon of the Momoyama period.

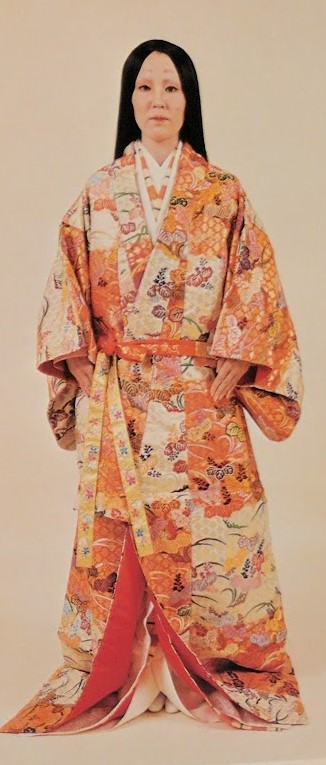

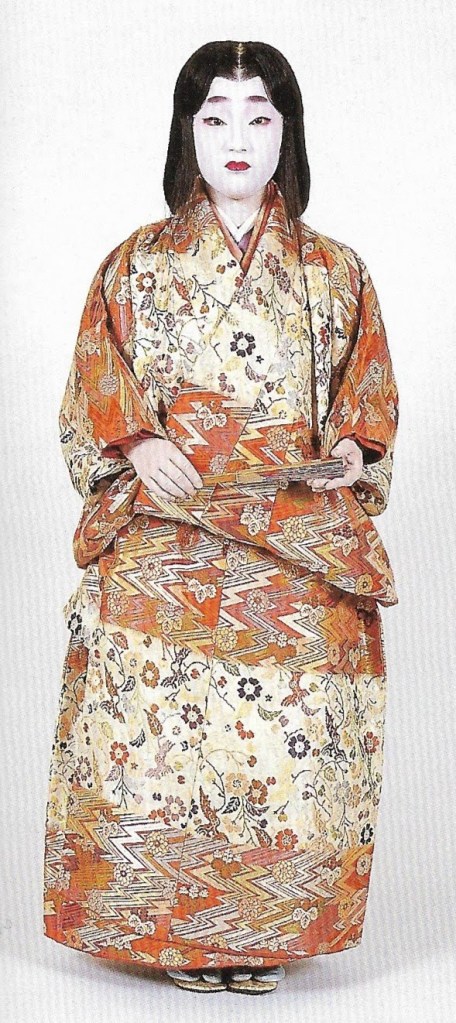

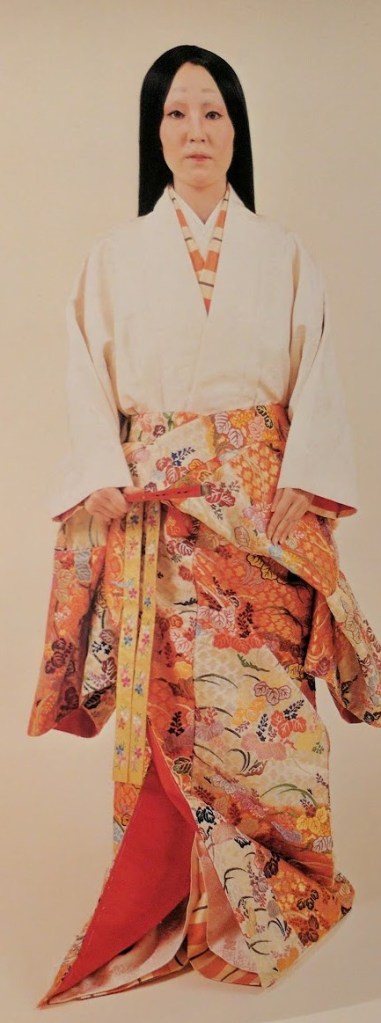

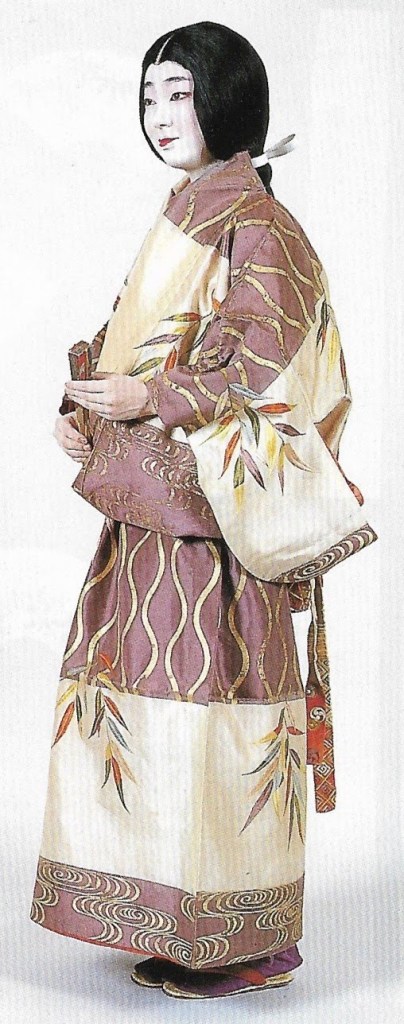

We have few intact extant women’s garments from this period; the garments shown below are museum-quality reproductions based on textile fragments. The term kosode is a general word for a garment with small sleeve openings; the following garments are all specific types of kosode. Most of these layers were made of silk; see the Fabrics section for the closest alternatives available today. Most of these garments can be found in the Patterns section.

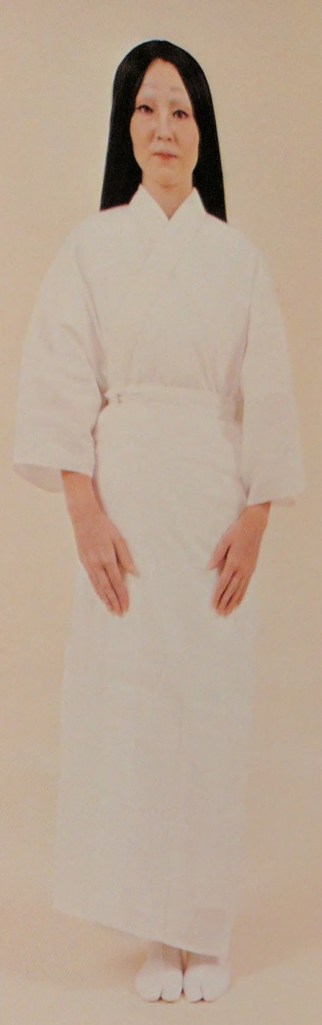

- Juban: after the Portuguese term gibão, the innermost visible layer. Today, a collarless hadajuban is worn underneath the juban. It is likely that this was worn historically as well, but it’s difficult to find information on this invisible layer. All underlayers are tied closed using white koshihimo (‘waist ties’)

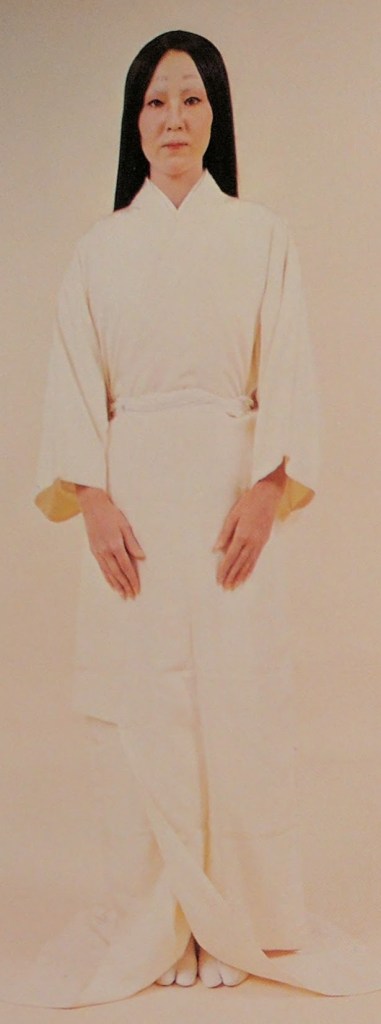

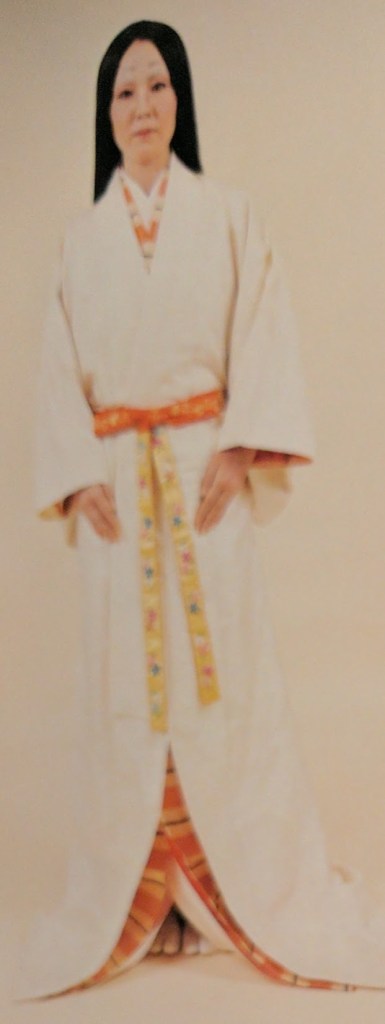

- Aigi/aidagi: (“middle clothing,” undecorated kosode used as visual spacing between decorated kosode, usually white or red

- Shitagi: “under clothing”, decorated kosode, usually decorated using tsujigahana (see Fabric Decoration section)

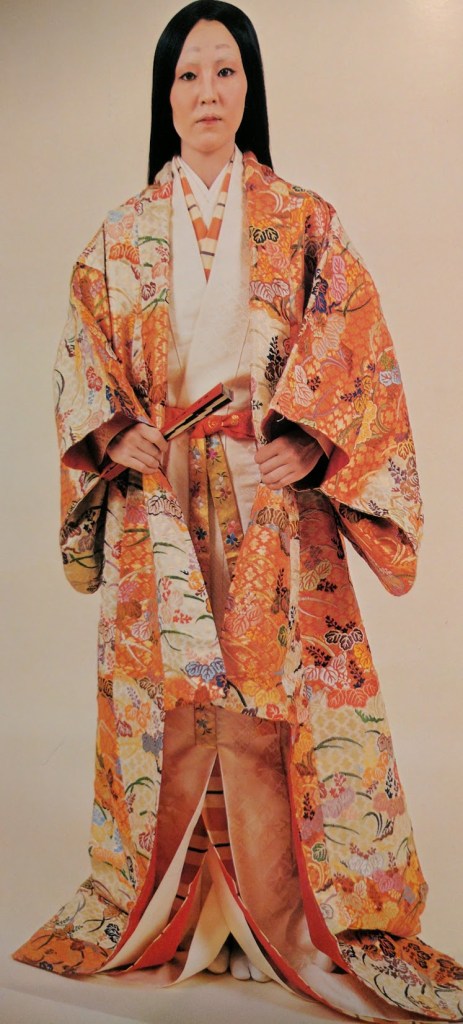

- Uchikake: “thrown drape,” extra long, highly decorated outer layer, could be made from a heavy brocaded silk such as karaori

In addition to being worn open as above, uchikake could be belted with a train, tucked short for outdoor wear, or worn down around the waist in warm weather.

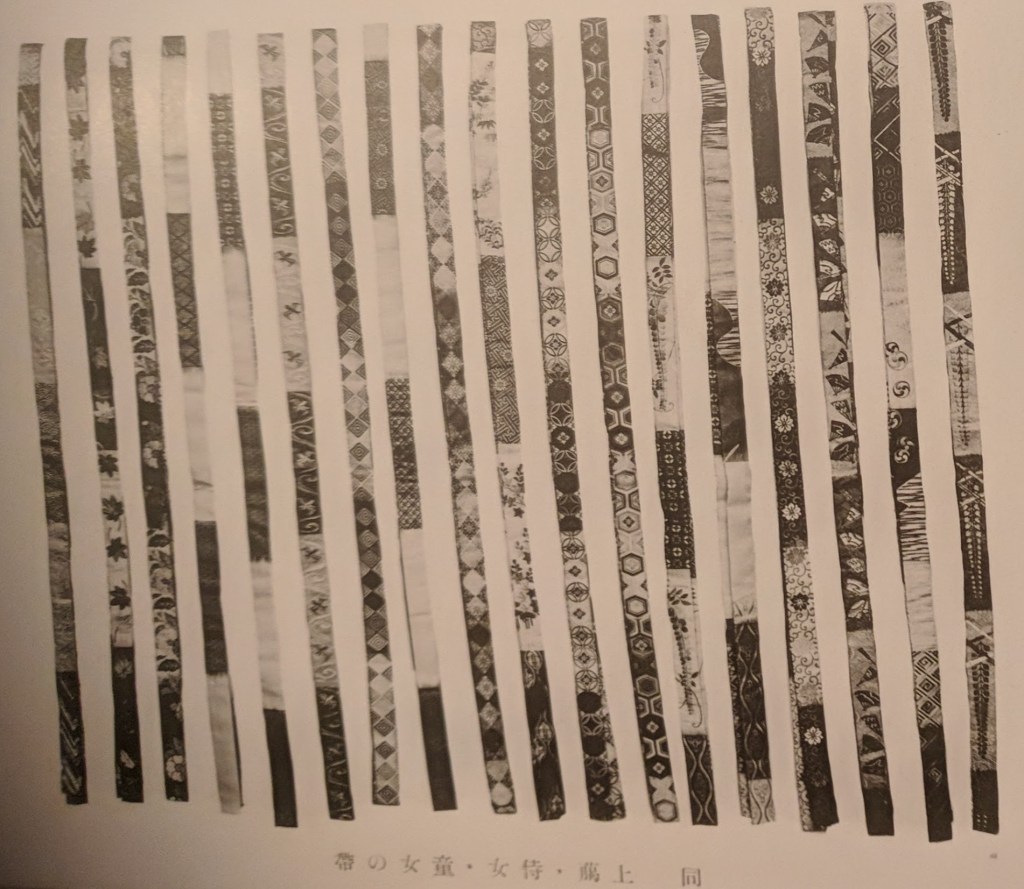

Most women would tie their sash (hoso-obi/’narrow obi’, also called kuke-obi/’slip-stitched obi’) in front, on the side, or tuck it up so it would not be seen as shown in the center image above. Young unmarried women would tie it in back, an echo of the integrated back ties on childrens’ ubugi. Hoso-obi were often made of brocaded or intricately decorated silk, and were approximately 2” wide. Place the center at your navel, bring both sides around to cross in the back, bring them to the front again to tie in a bow, then slide sideways if desired.

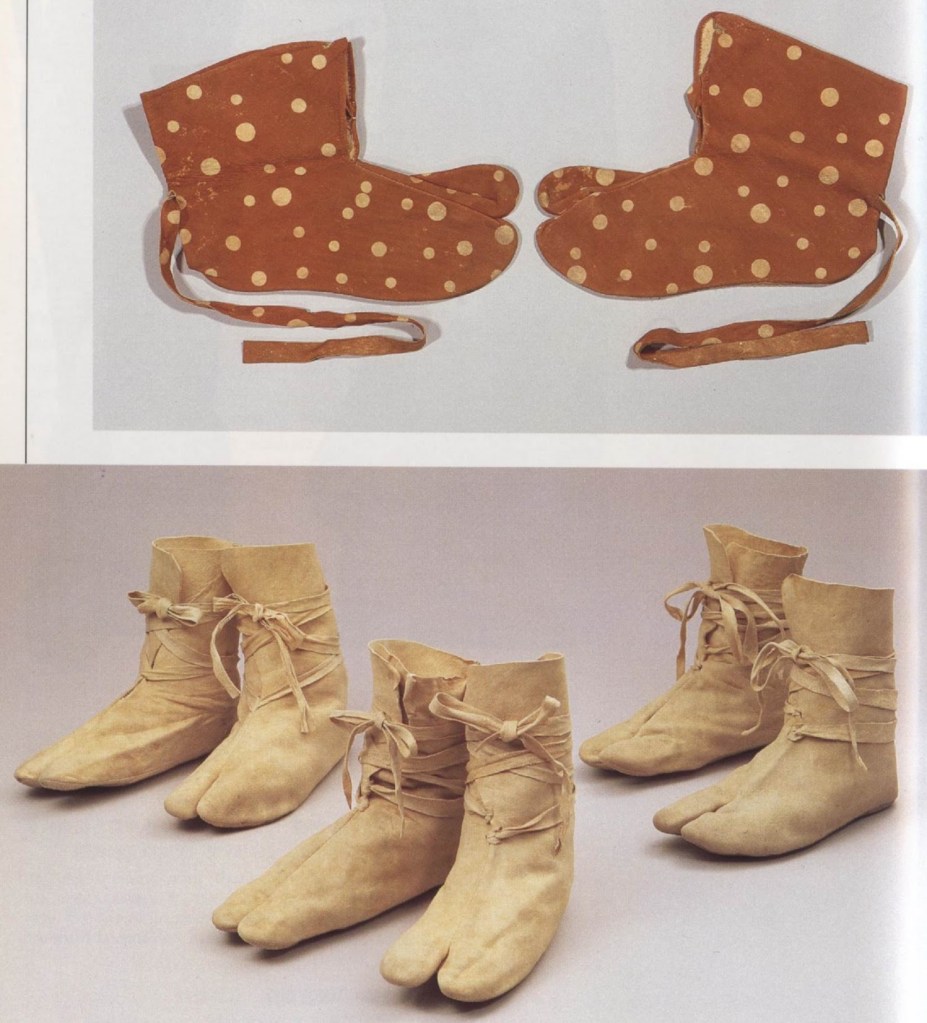

The white tabi here are from the Momoyama period, and the spotted are from early Edo. The construction is similar to modern tabi except that the opening is at the front of the ankle rather than the back, and they’re closed with ties which could be attached in various locations. Tabi colors seen in Momoyama ensembles include a wide variety of colors such as white, sky blue, golden yellow, and purple, and the material could be fabric or leather.

Zōri (sandals) are typically worn with these ensembles. The hanao (straps) were often red or white. These can be woven from rice straw (warazōri) or bamboo sheathing/take no kawa (takezōri). The latter are sold as “bamboo leaf” dumpling wrappers in Asian grocery stores if you want to experiment.

The long ponytail shown below is called suberakashi (垂髪). The shorter locks of hair in front are called binsogi no kami (鬢削ぎの髪) and are cut when a young woman comes of age. There are multiple variations in how it is tied, but typically the hair is first secured with a twisted paper cord, often black, called mizuhiki (水引). The paper hair-tying string of choice today, motoyui (元結い), was developed in the late 1600s; it’s similar to mizuhiki, but is treated with rice starch for a wire-like stiffness. Mizuhiki is sold online, but often has sparkles and wire cores that would not have been seen in the original versions. Hemp twine was used at earlier times and was still used by the lower classes. This initial cord tie is covered with a wider strip of Japanese paper called hōshogami (奉書紙). The hōshogami is cut into strips and folded into white paper hair ties called takenaga (丈長) at the time, and hira-motoyui (平元結い) today.

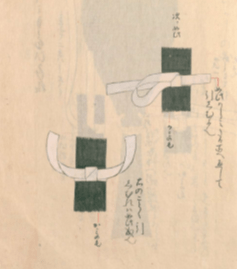

You may want to look up YouTube videos on Japanese hair styling, nihongami (日本髪) for information on tying these. While it’s extremely unlikely that any of the hairstyles you see date from before 1600, they almost all demonstrate how to tie motoyui, and some show hira-motoyui as well. There are several ways to make a hira-motoyui, but the simplest is to start with a ¾ to 1” strip of heavy paper or posterboard (hōshogami is 0.18mm thick) and fold as shown in the diagram below (read right to left!)

The join between one’s own hair and an extension can be covered using a brocade wrap called an onaga (尾長) secured by kumihimo cord or a similar cover made of hōshogami.

The white makeup below is called oshiroi (白粉), and is made from a mixture of rice powder and white clay. Please skip the historically accurate but very dangerous white lead! The intensity of oshiroi varied according to time, place, social status and occupation. Lighter variants call for applying it and then rubbing it off to create a natural, pearl-like sheen rather than a white pancake look. Either way, the white powder is mixed with water and applied using a wide brush.

Women’s portraits of this period normally show hikimayu (引眉), where the eyebrows have been shaved or plucked off and replaced with soot smudges higher on the forehead. The models in the Jidai Matsuri do not, presumably because the women modeling the ensembles were not enthusiastic about the idea of removing their eyebrows. In this portrait traditionally held to be of Yodo-dono, her hikimayu are drawn fashionably high, close to to her hairline, and the makeup other than oshiroi is subtle.

The bright red makeup is safflower red (beni/kurenai). The Benibana Museum has instructions on how to make your own red cosmetics. A brush is used to apply the red liquid.

The teeth are traditionally blackened with ohaguro (a mix of tannins, iron, and vinegar), as a final touch to this distinctive ideal of beauty.

References:

- Fukushokushi Zue. Shinshindō Shuppan, Ōsaka: 1969.

- History of Women’s Costume in Japan. Art Books Shikosha Publishing, 2003.

- Ise, Sadatake. Ise Family Reishiki Miscellaneous Volume 17 [7]. National Diet Library. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/2574333/1/29

- Jidai Ishō no Kitsuke. Genryusha, Tokyo: 1982.

- Kurihara Hiro and Kawamura Machiko. Jidai Ishō no Nuikata. Genryu-sha Joint Stock Co. Tokyo: 1984.

- Kyoto Costume Museum website. http://www.iz2.or.jp/english/ Accessed March 10, 2017.

- Marshall, J. “Soy Milk”. http://www.johnmarshall.to/H-Soymilk.htm Accessed March 14, 2017.

- Nihon no Bijutsu Vol. 39. Shibundō, Tōkyō-to : 1966-.

- Seki, Yasunosuke. Rekidai Fukusō Zuroku: Senshokusai Hen. Rekidai Fukusō Zuroku Kankōkai, Kyoto: 1933.

- Stinchecum, Amanda. Kosode: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection. Japan Society and Kodansha International, New York and Tokyo, 1984.

Leave a comment